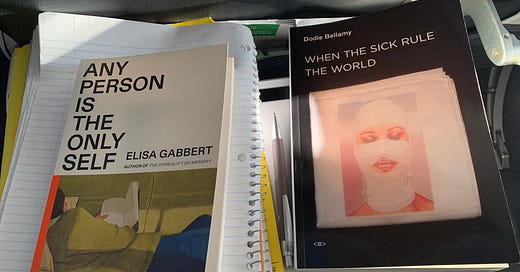

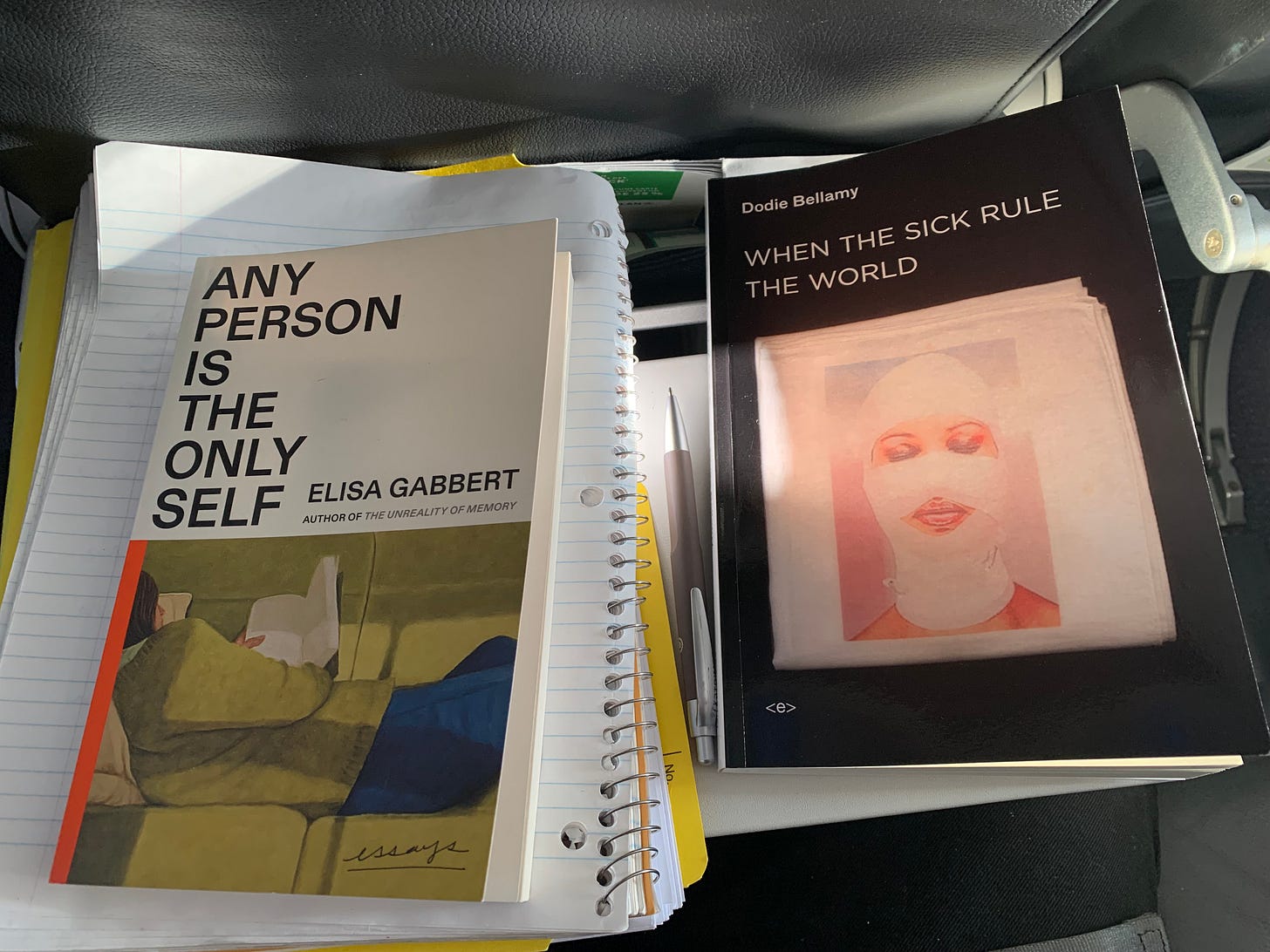

the green notebook,

, reading Elisa Gabbert on Sylvia Plath, + prose on illness by Dodie Bellamy + Christine McNair,

Elisa Gabbert has a couple of essays in this collection on Sylvia Plath that are quite striking, including one on the publication of a previously-unpublished short story that Plath composed during her collage days. In preparation, Gabbert reread The Bell Jar (1963), a book she couldn’t recall, as she’d read it “when I was fourteen or so.” I actually laughed aloud at this particular revelation, as she rereads this novel she hasn’t opened since teenhood:

Oh God, I thought, Sylvia Plath doesn’t understand how paragraphs work.

Having read the whole novel, I can confirm that Sylvia Plath doesn’t understand how paragraphs work.

In the end, Gabbert still considers Plath’s novel as simultaneously imperfect and perfect, with moments that seem horribly dated, and yet a work of unmistakable genius. Plath’s short story, in turn, is no more than it is: a previously-unpublished short story by a writer during their college days. Should it have appeared in print at all? There’s an argument made for study, but perhaps not general readership. I, myself, have always attempted to keep every draft and manuscript, finally able to send nearly one hundred banker’s boxes of material over to the archives at the University of Calgary since 2008. Will anyone be wishing to publish any of those early attempts, or even wish to go through a box-worth of my teenaged notebooks? Most likely not. I would certainly hope not. There isn’t anything particularly embarrassing in any of those boxes, it would simply be terrible writing, alongside a wealth of dead phone numbers and mailing addresses. If anything, I wouldn’t begrudge any of my descendants attempting a buck or two on any of it, but I would just hope to be long gone by then.

I don’t think Gabbert’s observation on Plath’s paragraphs takes anything away from Plath, but offers, instead, an insight into structure, shape, style. It says something of Gabbert’s own progress as a reader, and perhaps, also, of time, which all writing, one might say, inevitably is.

*

It is interesting to connect the swirls, or at least feel them surround each other, across this brief temporal expanse: Dodie Bellamy’s prose on illness, Elisa Gabbert’s essays on Plath that speaks both to Plath’s work and her depression, suicide attempts and eventual suicide, and Christine’s health crises at the core of Toxemia. “When the sick rule the world roses, gardenias, freesias, and other fragrant flowers will no longer be grown.” writes Bellamy in the title essay of her collection, a piece that opens with a quote by Plath. “On Valentine’s Day the sick will give one another dahlias and daisies to say I Love You. The sick should have sex as often as possible because it’s good for the immune system.” In a passage referencing one of Plath’s attempts that provides Gabbert her title, she offers:

After rising from the ashes of the crawl space, the thought of death now unwished for, out of her own control, seemed cruelly unfair, the act of “malicious gods.” “This can’t happen to us,” she thought; “we’re different.” Different why? Because we are we, not them. Any person is the only self.

Or, from Christine’s Toxemia:

I used to think I’d be a great martyr. I tried to martyr myself sometimes and it never turned out well. I really don’t want to write this. I really don’t want to write this or be here or think this. I’m going to die still shifting between calm and storm.

You are so hard on yourself, he says. It’s not fair.

I know it’s wrong. I know it’s wrong. I know it’s wrong.

*

I also discovered this within the layers of Christine’s Toxemia, once the final book had landed: “When I met my husband, it was disconcerting. He had such lovely eyes. But he was loud. So loud. And asked questions that were too personal. And loud. And social. It took us a while to become friends, to find each other’s middle point.” Now I make a point of approaching her to present her the opportunity to look at my eyes. Until she realizes what I’m doing, and pushes me aside. Rolls her eyes. Threatens to poke mine out.

He makes me laugh. I don’t laugh enough. Never was a kinder look. His eyes – his beautiful eyes.

*

We drive home from a Saturday walk-in clinic, where Christine went to attend some chest pain she’d been having, as she now takes so much longer to shake anything. Two weeks with a cold, for example. She’s fine, but some chest pain and a lingering cough, sounding awful all week, laying fallow from work. You can’t die until I’ve been to prom, says Rose from the backseat, unprompted. You can’t die until I’ve begun my period, says Aoife in response. I’m not going through that alone with him, she adds, waving her hand in my direction. Fair, I thought.

Christine: I’m not going to die!

Thanks for that, Rob. Death and the intimacy of the family. What could be more satisfying and important.