I sit in the dark and I wait. I sit in the dark and the children are sleeping. Two-year-old curled up shell-shaped on my hip. Newborn in her side-carred crib, sleep-twitchy and precious. I’ve called my mother. It’s 4 a.m. I wait in the dark because I worry I’m dying. I don’t wake my husband yet, will do so closer to my mother’s arrival. I don’t want to die between my children. The bps are up and my feet twitch. My brain lit up and hard electric, the same as before. The pain in the side. The brain lit up and electric and a pressing sense of doom and headache in the bones that goes on and on and won’t stop. The numbers on the clock double themselves up and dance around. The brain is lit up and my legs twitch, and the aura I remember from before from so long before, from the seizures as a kid, and the seizures when I was bulimic, and the seizure after playing the fainting game. The sense of cliff. Brain is all lit up with pain and I worry I’m dying and I don’t want to seize between my children and there’s nothing but waiting in the dark and it all takes too long and I’m waiting.

I sit in the dark and I wait. I sit in the dark and the children are sleeping. Five-year-old curled up shell-shaped on my hip. Three-year-old in her side-carred crib, sleep-twitchy and precious. I’ve not called anyone. It’s 1 a.m. I wait in the dark because I worry I’m dying. My husband isn’t here, he’s taking care of my father-in-law at the farm. I don’t want to die between my children. The bps are up and my face tingles. A pressing sense of doom that goes on and on and won’t stop. The numbers on the clock double themselves up and dance around. The brain is dark. The sense of cliff. Brain processes weakness and tingling and I worry I’m dying and I don’t want to die between my children and there’s nothing but waiting in the dark and it tall takes too long and I’m waiting. I turn on my side and turn on a meditation app. Pour lavender oil on my throat.

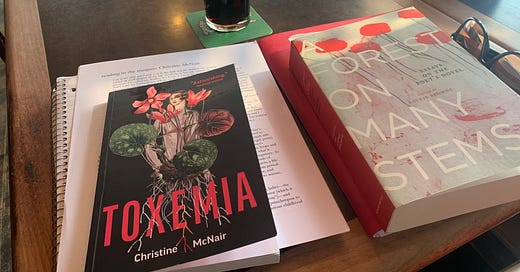

The final, finished version of Ottawa poet and self-described book doctor Christine McNair’s hybrid/lyric memoir, Toxemia (2024) recently landed upon our doorstep. Is a writer allowed to discuss their partner’s work in such a way as this? This is Christine McNair’s third full-length title (and her first finished work begun before our children were born), following two full-length poetry collections, Conflict (2012) and Charm (2017), all three of which were published by Toronto’s Book*hug Press (the press formerly known as BookThug). Composed through rhythmic loops and echoes, medical research and lyric memoir, Toxemia is named for the outdated term for what is currently known as preeclampsia, a potentially fatal multi-system disorder specific to pregnancy. As the website for the Preeclampsia Foundation Canada describes the condition: “Thousands of women and babies get very sick each year from a dangerous condition called preeclampsia, a life-threatening hypertensive disorder that occurs only during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Preeclampsia and related disorders such as gestational hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia are most often characterized by a rapid rise in blood pressure that can lead to seizure, stroke, multiple organ failure, and even death of the mother and/or baby.”

She went through this not once, but twice, following the births of our two young ladies in 2013 and 2016—the five percent of five percent chance of it occurring after the baby is born, instead of prior (which is what occurred twenty-plus years earlier around the birth of my first child, back when it was still called “toxemia”)—and McNair describes both the life-threatening condition and effect in detail, writing on preeclampsia to her subsequent stroke, weaving in elements of her long history of depression, and various childhood traumas and illnesses. Throughout the narrative, she collages and weaves through her first-person recollections various threads of archival research, photographs, cultural references, Victorian and other historical medical information and illustrations. She invokes the fictional Lady Sybil Cora Branson (née Crawley), who died in childbirth from toxemia at the end of the third season of Downton Abbey (2010-2015). She speaks of nesting dolls, and tracks a handful of her genealogical lineages, including the lack of information on her maternal great-grandmother who died at thirty-six or thereabouts, just before or during the Second World War, and her great-grandfather’s second wife, who died soon after, history having lost her details, including her maiden name. She speaks of her paternal grandmother’s history of depression, a story never told or connected during her own teenaged years, when her depression emerged. She answers potential questions for her newborn children provided through a parenting app.

She speaks of working on this manuscript while at Sage Hill, twice heading into Emergency, and doctors that looked upon her and her symptoms with suspicion.

In a Facebook post after a day reading through Toxemia, Sudbury writer and critic Kim Fahner wrote: “When things fall apart with our physical health—and I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately—how do we manage, survive, and still flourish as we face chronic illness and disability? How do we mind our mental health as our physical health becomes uncertain and increasingly problematic? How do tend to (and care for) our human selves when we’re caught up inside a frustratingly inhuman medical system?” She continues: “McNair’s Toxemia raises key questions, too, about how we define and redefine ourselves throughout the course of our lives.”

McNair’s writing has always had an edge, but Toxemia employs a further level of visceral, with the strength and wisdom of knowing when to write directly and when to write slant, a multitude of blended lyric threads. She examines layers of her own past history, interweaving information on women’s health and health-approaches (and dismissals), to attempt a handle on exactly where she is now, moving through motherhood to illness to disability. If her first two collections employed an underlay of “riot grrrl” rage, the agency she works to articulate and claim through Toxemia are far deeper, darker and scientific in approach. “If you go into any subject in depth,” she offers, “you fall into the things you’re trying to avoid.”

endo

When I did have my stroke, it was a mini-stroke, it was transitory. Transitory ischemic attack. Mini-stroke. Cute stroke! Warning of Impending Actual Stroke. Doom Gloom.

Should be brief but mine wasn’t exactly. Should create no damage but mine maybe did or maybe it was the meningitis. Flash white on the brain stem, only sum. Residual numbness on the right side of my face, two years later. Weaker on the right side.

Something not quite right there.

The body isn’t, I mean.

You’re not right, you know.

You know it.

Carved into sections within sections, with a narrative comparable to a prose collage accumulation, the book is structured with opening “invocation” followed by four section-clusters—“symptoms,” “presentation,” “risk factors” and “treatment.” Medically aware and lyrically astute, McNair works to decipher her growing patient file, and her developing swirl of interconnected illness, disability and motherhood. “My children root to stories with dead mothers and sick mothers. Any orphan. They grip my arm. When visiting my father and his wife,” she writes, “they go to the farmers market to buy corn while I’m in hospital. They sob when the produce is put in the trunk. They want to hold it like Mei in Totoro. They want to carry me secret love messages carved into corn. They want to imagine up a cat bus and don’t understand why it doesn’t come.”

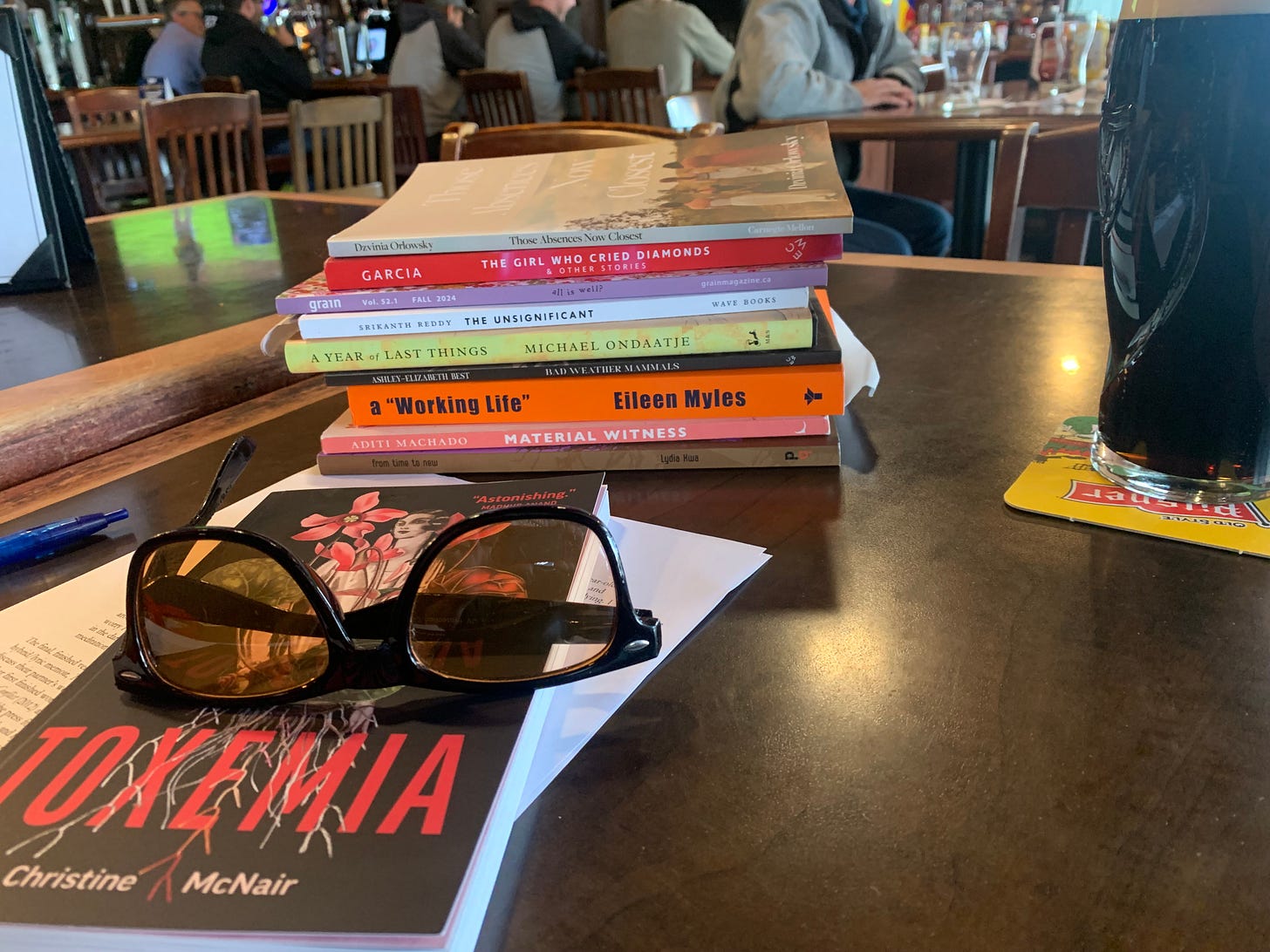

As a motherhood memoir, Toxemia exists as counterpoint to three other poet-memoirs out the same year: the straight narrative lines of Ottawa poet Katherine Leyton’s Motherlike (2024), Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber’s hybrid essay collection, Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood (2024)—writing the messy business of motherhood, acknowledging the blood that accompanies this kind of beauty—and Picton, Ontario writer Zoe Whittall’s unfurling prose-poem narrative, No Credit River (2024). While each of those volumes explore elements of motherhood, trauma and mental health, the visceral elements explored through a language more deeply attuned to this particular blend of lyric and staccato sound, collision and shape provide Toxemia a connection to the structures of Toronto writer Bahar Orang’s Where Things Touch: A Meditation on Beauty (2020), and, more overtly, Toronto poet Margaret Christakos’ Her Paraphernalia: On Motherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (2016); there might be blood, but there is an ear attuned to the swirls of language that might otherwise be called playful, but for the subject matter (and still might be). As McNair’s page-long “presque vu” includes:

At least there are visible growths on my heart. Nodules. Clots. Vegetations. Depends which doctor you ask as to preferred terminology. Non-bacterial endocarditis means no fever, means an underlying reason. Lupus. Metastasized cancer. Blood-clotting issue. Thrombophilia. My body loves clots.

Thrombo, the clotting of blood. Philia, love. My body loves clots. I am thrombophilic. We hope I am thrombophilic and the blood thinners will fix it. I heart clots.

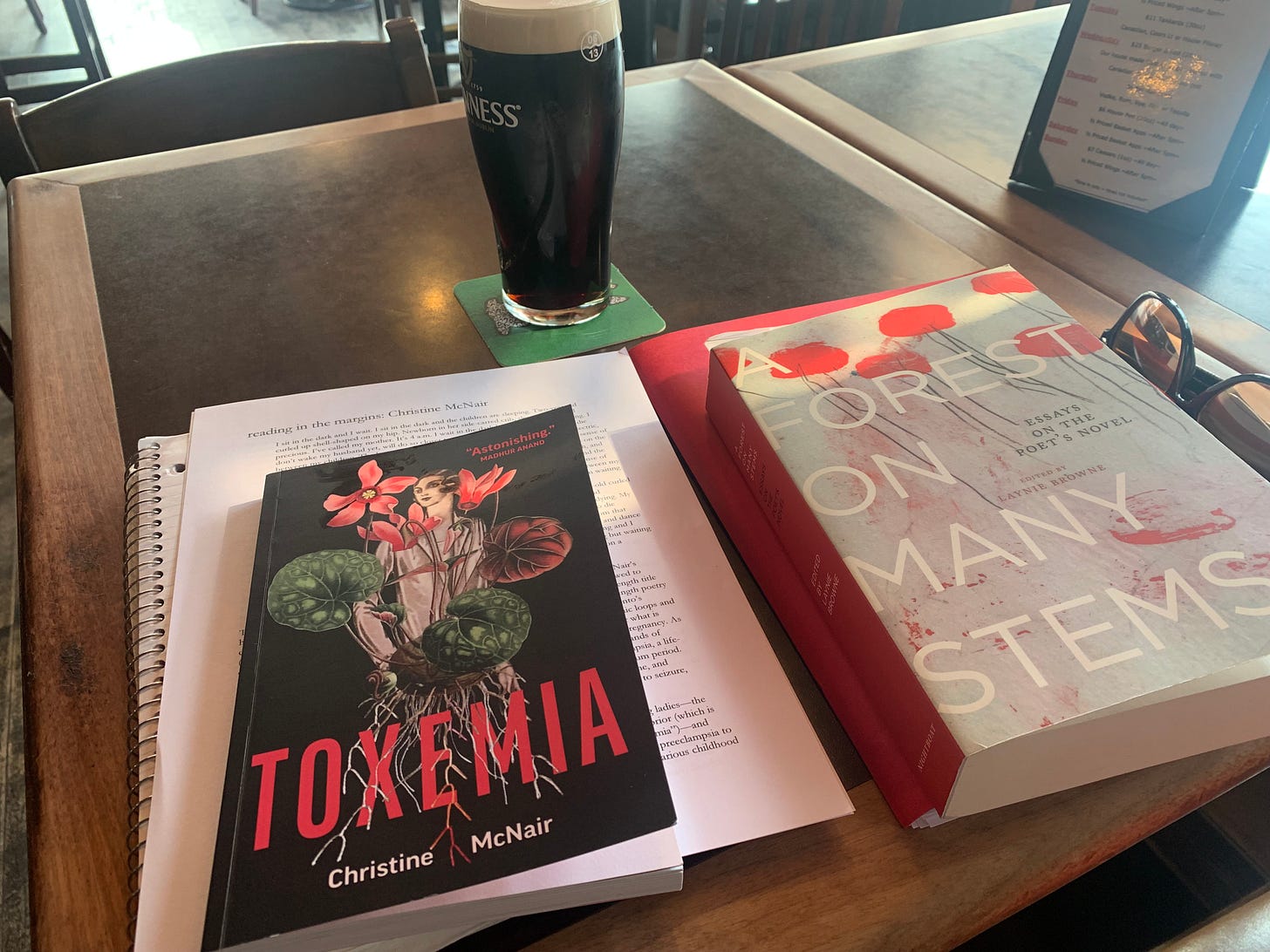

Toxemia’s particular poet-memoir blend also invites comparisons with a handful of illness memoirs by American poets, each of whom work prose/hybrids with an obvious lilt towards lyric and language, from Sarah Manguso’s The Two Kinds of Decay (2008) and Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (2009), to Anne Boyer’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Undying: Pain, vulnerability, mortality, medicine, art, time, dreams, data, exhaustion, cancer, and care (2019) and Heather Christle’s The Crying Book (2019). In the introduction to A Forest on Many Stems: Essays on the Poet’s Novel (2021), editor Laynie Browne asks a question entirely relevant to this conversation: “Why do poets turn to prose? And within the oeuvre of any given writer (one who writes both poetry and prose) what is the relationship between the two forms? What purposes does prose fill that poetry perhaps does not?” Perhaps, as much as wanting to explore and process trauma and experience, the shift towards prose might provide an added layer of narrative time, as Manguso wrote as part of The Two Kinds of Decay:

Getting sick was a process just as getting well was a process.

The most important things must happen slowly, incrementally.

Through Toxemia, perhaps moreso than with her prior poetry-specific titles, McNair’s work in this collection exists in direct lineage to the work of Christakos, with further echoes that might connect to the detail-oriented language intricacies of Sault Ste Marie poet Shannon Maguire, Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris and Ottawa poet (via Saskatchewan) Sandra Ridley, a way of writing that appears to simultaneously write trauma through language and language through trauma, threading the needle from both ends. Each of those poets, including McNair, approach writing as a form of study: turning a subject around and inside-out, and offering the form of the lyric as both process and reportage. “Things that might predispose me to preeclampsia: my blood type (AB+),” McNair writes, mid-way through the book, “my age, my weight, my previous history of preeclampsia, my PCOS, my history of childhood seizures, my mother’s high blood pressure, my father’s high blood pressure, my asthma, the suicide attempt in my teens that may have damaged my kidneys, my husband’s history of fathering preeclamptic pregnancies, the interval between pregnancies, my baby’s DNA.” There’s a precise way through which McNair describes her experiences, offering a language both exact and lyric/abstract, propelled by the sounds and shapes to reveal what a direct line never could. In an essay on Toronto writer Michael Ondaatje’s classic novel Coming Through Slaughter (1976) included in the anthology A Forest on Many Stems, American poet C.D. Wright (1949-2016) opened by writing: “A book that follows its nose, trusts its nose, a book that has its own rhythm, its own melody; a book that opens with a damaged photograph and a quote from a long-dead musician from the band of another long-dead musician along with three sonographs of a dolphin. That’s how it starts. Under the tent-flap of poetry.” A bit further along, Wright offered sentences most of which could apply to Toxemia:

Coming Through Slaughter does not walk through its paces as a full-fledged story, but frames up like a score and segues like a film and phrases like a poem. A short paragraph is a page; a paragraph is an entire scene. Every paragraph is a polished work. He is building his poem. It is wrapped in a novel.

I’ve heard McNair read from this collection three times so far, including twice prior to the official Ottawa launch, listening to her reading style evolve from the initial energies associated more with her previous collections, that explosive, pent-up rage, into something broader, thoughtful, more specific and more directed; not the urgent collateral of her first two collections, but something clear, nuanced and purposeful, although with no less force.

Responding to an email on the collection (from the other room), McNair offers her thoughts on the book:

I was lucky enough to spend time at Banff during the final edits of Toxemia at the Winter Writers Retreat (2023) with mentors Nasser Hussain and Lisa Robertson. I used much of the alone time to complete edits and tweak with structure of the book while also trying to frantically produce new (other) work. I read through Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and also Bahar Orang’s Where Things Touch as examples of mixed genre books. I read through a Nicole Brossard work in translation (Mauve Desert). I read Theresa Hak Kyun Cha’s Dictee. I was working with my editor Tanis MacDonald’s notes and trying to figure out the final shape of things. I'd worked with Tanis at Sage Hill prior to the book’s acceptance by Book*hug when I was in her 2019 non-fiction workshop where many fellow participants were working hybrid texts.

A work that became stuck in my head both before and after Banff — maybe unexpectedly — is Michael Ondaatje’s 1982 memoir Running In the Family. It is very firmly a memoir (where I feel Toxemia fits) but it isn’t a straightforward text. He makes use of photographs and fragments and time jumps and magic realism. I read it for the first time during my undergraduate degree at Acadia where I ended up completing a mixed genre (short fiction/poetry) creative writing thesis under Dr. Wanda Campbell. (She strongly encouraged my instincts to colour a bit outside the lines in terms of the final form of my thesis.)

Nasser challenged participants at the end of the writing retreat to incorporate a visual aspect to our group reading using PowerPoint. I used PowerPoint to align my reading with images from the composition of the book and from my various medical crises. Images with scraps of 16th century obstetric texts along with my daughter’s baby clothes up for sale and myself reflected in hospital surfaces from the Very Bad Year and other life debris. An online Facebook quiz of Which Downton Abbey Character Are You? (Sybil Crawley). Images of the canary girls working with WWI munitions. When I returned home, I knew that I needed to ask Book*hug if they were amenable to adding photos to the final manuscript. I could see the final shape.

Toxemia is a hybrid text yes but at its heart it is a memoir. I play with language and shape on purpose. I play with fragments. But there are much more straightforward lyric essays mixed in with the parts that lean playful. The book dissects stories and family and the body. I do see it as a poetic memoir rather than a book of pure poetry. Language is important to me in both prose and poetry and this book flexes between genres on purpose. Play can be found in prose, even non-fiction prose, even a memoir, even a health-historic-body-fueled memoir filled with tough things.

This is great. Thank you for pointing me to it or it to me.

Great write-up, Rob!