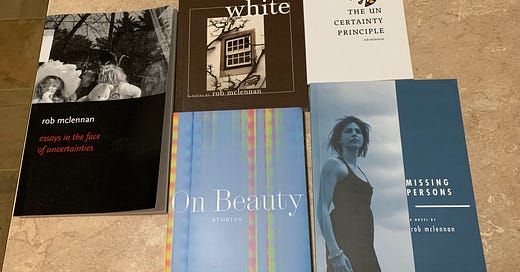

the opening of my second novel, Missing Persons (2009)

, and the origins of my character Alberta, more recently seen in On Beauty: stories, (2024)

Here’s the opening preface of my second published novel, Missing Persons (Toronto ON: The Mercury Press, 2009), a title that followed white (The Mercury Press, 2007). I thought it would be interesting to show this as a connector between a handful of stories in On Beauty (2024) [one of those stories here, for example] to where the character Alberta had been, prior. This is where she began. I’m currently working a novel in which Alberta is even a bit further down the line than in On Beauty, which I’m finding rather interesting. Where else might she land? Strange to be writing a character for so long, originally conceived of around 2000 (nearly a quarter century ago, for those keeping track) for a novel project that never came to fruition, properly emerging in that failed project’s prequel, Missing Persons.

If anyone interested in copies of Missing Persons, or white (with the publisher long defunct, copies are best found directly through me), they’re available at $15 each (add $2 for postage; outside Canada, add $5: paypal/e-transfer to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com or use the paypal/donate button at robmclennan.blogspot.com). Or, if anyone signs up to be a paid subscriber for this glorious substack of mine (between now and the end of December), I can simply mail you a copy [once the Canada Post mail strike is over, naturally].

Either way, here’s where the character of Alberta, at least in print, began:

Some people live in two places.

The first time Alberta Jonas disappeared, she was six years old. She slipped behind the barn and over the lump of earth they called hill and walked south through the water hemlock and dead leaves, away from the poplar and spruce, until she was out of sight of the house. She lay down in a field.

That first time, there was no wind. There was only the air, hanging passive as blue curtains melting into the ground. Heavy and sticky and useless to fight against.

She pulled out the two tight braids she had made her mother weave in her dark hair. Alberta lay on the ground with the dirt in her tangle of hair and pricks of the second cut along the backs of her legs, and her spine and stared up.

As big as the world, twenty-two kilometres in any direction, the blue was infinite.

She was small, a speck in the rough work of dry prairie, where winter cracks your lips bloody, and an unbroken wind from the rocky mountains, with the help of dust or snow, flays the skin from your very bones.

She knew only what she could see.In the small house of hewn logs and echoes of sod where she lived, Alberta's mother's water broke.

Huff huff huff of breathing, steady succession, bursts of light and dark. Emma. Too late for the truck to deliver her to town. Alberta’s father was nervous, but he did not panic. He remained almost mechanical. He did the appropriate things—blankets, hot water, damp cloth for his wife's head. A soothing voice like velvet rope for her to cling to. So she would not fall.

At her age, what dangers they had entered into.

Her father had been witness to childbirth before, of cousins, siblings and his own sweet daughter. Her father had wanted to wait until they were in the new country before they had children. Starting well past when his brother had, or any of their neighbours, well on their way to further generations.The first time, Alberta disappeared without warning and with barely a notice.

Before her mother had begun to burst. Before what was no longer one had not yet become two. Neither caterpillar nor butterfly; a chrysalis.

Alberta drifted in circles. No one lived close. Homestead blocks of houses. Dots she could see, too far to walk to. The yellow school bus chugged down the long road to collect her. There were miles between stops. Slow turns at right angles, the direction home of north, east, north. Long turns that could be seen forever.

Lying on the cold ground, her fingers made tracks in the cracks in the earth. Her fingers wrote speech across the scars. She listened for birds, and for trucks. She listened for her parents to call out her name, for what would never come.

She had spent the morning flipping through the atlas, looking at the pictures, places she knew as familiar and unfamiliar. Winnipeg, Regina, Quebec City. London. Words she could not yet read. She studied shapes, lying on her stomach and turned pages.

Her mother had emerged from their kitchen and snapped at her, and she made off.

Lying prone in a bed of crickets, Alberta remembered a place her father had mentioned called Seven Persons. She wondered if it really existed, and if it held only seven people. If anyone had to leave when a new person was born, or wandered too close to town.

She thought to herself, if she would live anywhere, she would live in One Person, in the village of Her.