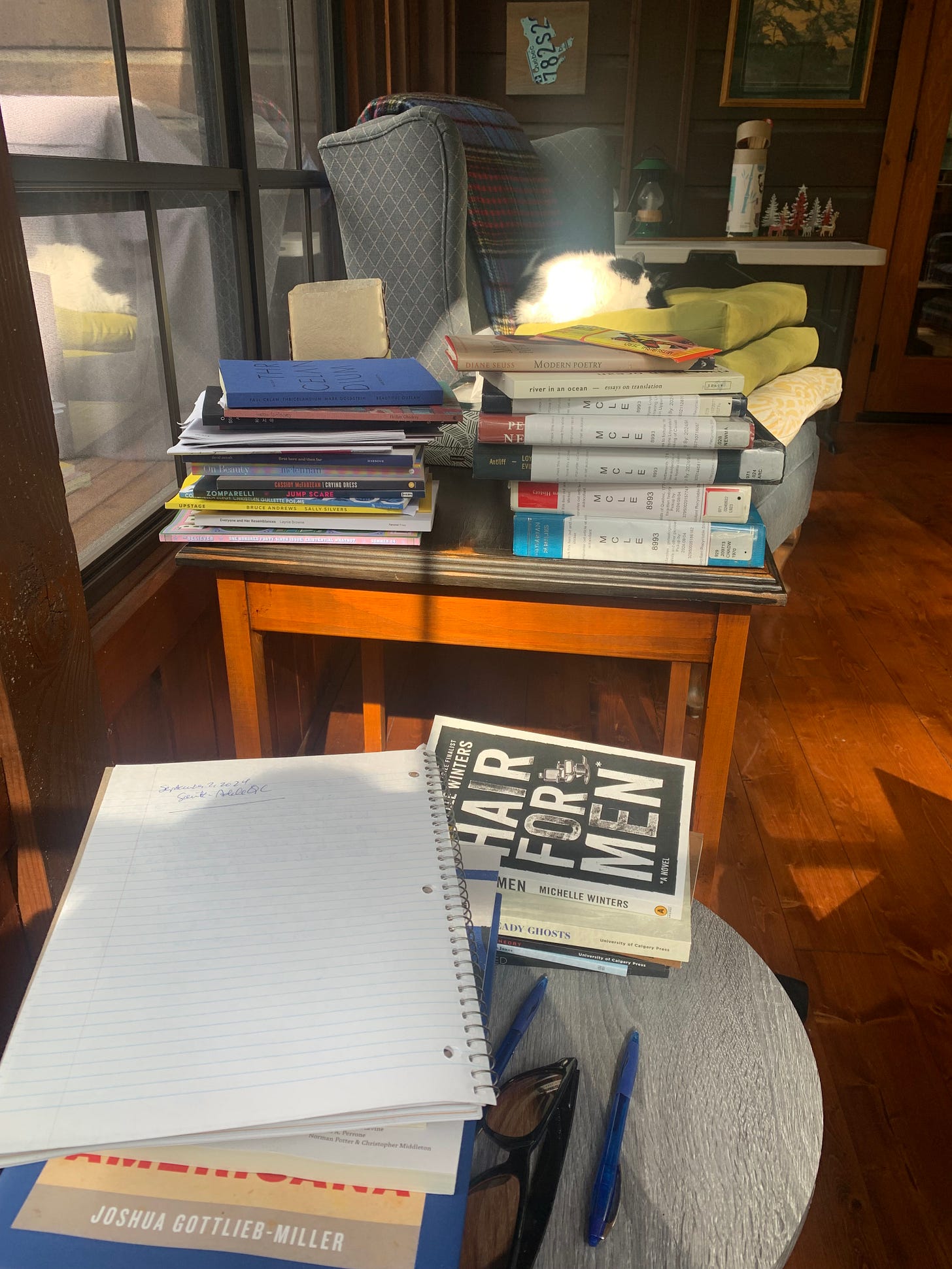

This morning, I work through galáxias (2024) by Haroldo de Campos (1929-2003), “one of Brazil’s foremost avant-garde poets,” as translated by Odile Cisneros with Suzanne Jill Levine, Charles A. Perrone, Norman Potter and Christopher Middleton. The poems are long-lined, expansive and descriptive, composed via an endless lyric of details on the ground across an excess of world travel. The book is described in Cisneros’ introduction (written in Edmonton, of all places; apparently Cisneros teaches at the University of Alberta) that “Campos suggests in his notes to the poem that the ‘semantic backbone’ of galáxias is ‘travel as a book, and the book as travel.’” As Cisneros writes, de Campos blends words from different languages in his lyrics, comparable to the work of Paul Celan, or George Herriman’s (1880-1944) work through “Krazy Kat.” As de Campos, through this particular translation, writes:

will decipher for a confused clot of old ladies a behatted old bunch

made in usa the derelict hebrew letters bleak plundered walls

There is such distance travelled through these pieces, one that offers an intimacy of people, thinking, reading and encountering. I’m curious as to how this might relate, if at all, to Uhart’s crónicas, both very different than the English-language travelling journal or memoir. What might have prompted such literary movements, such trajectories, across elements of South American Spanish-speaking literature? As Cisneros’ introduction to galáxias provides:

galáxias could be seen as a “traveling book” in yet another way: a vade mecum (Latin for “go with me”). “[A] baedeker of epiphanies,” Campos writes, referencing the nineteenth-century guides published by the German tourism pioneer Klaus Baedeker. galáxias offers readers a curated roster of iconic sites: New York’s Statue of Liberty, Stuttgart’s Staatsgalerie, Prague’s Charles Bridge, and beyond. Countless artworks and artists are also depicted: Gaudier-Brzeska, Brancusi, Cranach, Kienholz, and more. In a way, galáxias is chock-full of tips for the actual or armchair traveler and reading lists for lovers of world lit: Homer and Catallus, Shakespeare and du Bellay, Bashō and Buson, Pound and Joyce. Beyond geography, galáxias also maps out linguistic wanderings and crossings between Portuguese and other languages.

*

Online, through The New Yorker, I catch an interesting article on novelist Danzy Senna, by Julian Lucas. Senna, the daughter of poet Fanny Howe, is another I’d been unaware of, although I spent a great deal of my thirties immersed in her mother’s words. “The Hancock building // contains the Hancock building,” Howe writes, as part of the collection Emergence (2010), “the way the world appears complete, // and all sins hidden. / When you are gone, I go on // but when you return, I’m full of / questions, as if // I didn’t understand anything.” By my forties, I’d moved over to the work of Howe’s sister, Susan Howe, and her own temporality through prose; which, in turn, couldn’t help but impact my own process.

I’m curious by the descriptions of Senna’s work (although details that appear to focus solely on the social politics of her narratives, and little in the way of her language), and amused at Lucas’ account of the two of them posing as a couple to wander multi-million dollar open houses, almost as a kind of research, a connection to Senna’s ongoing work. “Our first stop was an open house in Pasadena,” Lucas writes, “a three-million-dollar colonial full of cream-colored furniture and bland art. ‘Does a basketball player live here?’ Senna wondered, gawking at the altitude of a marble countertop.” It’s a detail I’m quite taken with, although this particular tidbit struck as well, later on:

Her family is lousy with writers—not only her mother, father, and husband but her sister, her aunt, and, most recently, her nephew—though they try to keep their work to themselves. “There’s a misconception that we’re living in a literary salon,” Senna told me. “We’re actually living in a house with two teen-age boys who are completely the focus of our attention.”

The notion of the familial salon is an interesting one, although I suspect a rarity. Writer-spouses Joan Didion (1934-2021) and John Gregory Dunne (1932-2003) were certainly involved in the creation of each other’s work on an intimate level, and Bill Whitehead (1931-2018) was always first reader and editor for his partner, the novelist and playwright Timothy Findley (1930-2002), but not every writerly couple lives as such, nor might they wish to. There are always other things to attend.

Rose, who did assist with the final edits of two short stories in On Beauty. Her elder sister, Kate, who helped clarify the ending of my second novel, Missing Persons (2009), during her own teenaged years, a rare Saturday she asked what I’d been up to, so I gave an honest answer about feeling stalled in the manuscript.

The rare times when Christine or I might ask the other to look over something, often at that point of knowing something is required, but not exactly what.

*

Someone on social media wishes German filmmaker, actor and writer Werner Herzog (b. 1942) a happy birthday, offering this quote, attributed to him:

Civilization is like a thin layer of ice upon a deep ocean of chaos and darkness.