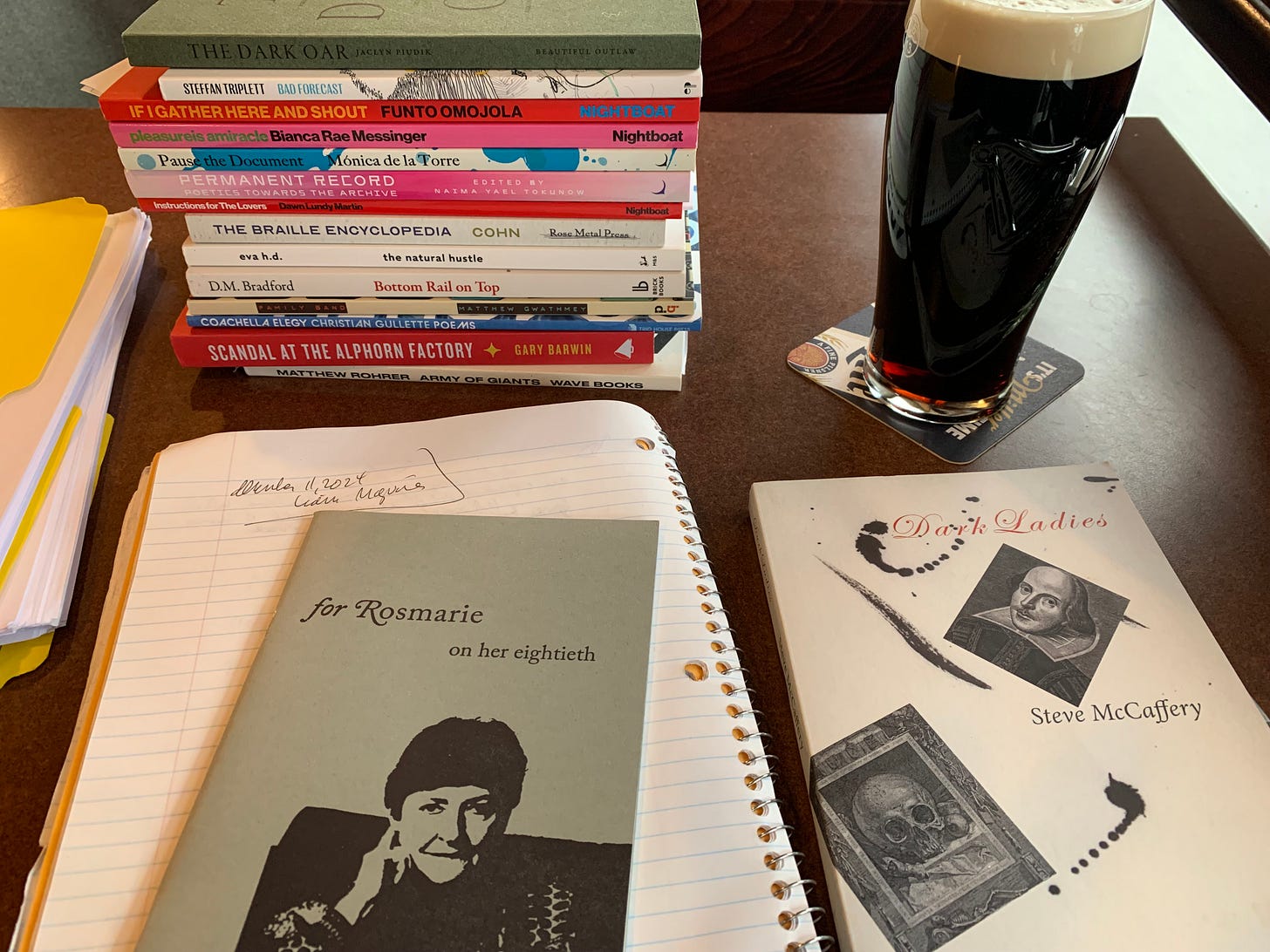

the green notebook

, reading Steve McCaffery's Falstaffe, + echoes of Perchta, Berchta, Mother Goose + Frau Holle,

I recently found a copy of British-born Canadian poet and critic Steve McCaffery’s Dark Ladies (2016), an expansion of William Shakespeare’s sonnets into experimental prose-blocks. I’m curious as how I hadn’t heard of the publication as it appeared, most likely distracted by toddler and newborn during those days. Here, too, the grey sky. “There’s nothing like a grey, damp sky to keep you in touch with your pessimism,” he writes, looping in and around lines that mention Falstaffe, replicating the spelling variation Shakespeare used in those original folios. “If we each admit that life’s become a tragedy a continuous present and that Death only deals in friendly takeovers then suddenly our galaxy will seem collectible. Don’t worry, with youth no longer on my side, and being pretty well ballasted with bull beef, I’ve every right to be wrong.”

From McCaffery’s hand: this mass of text, more than could ever be contained in quatrains.

*

The overhang of fog begins to lift, the sun lifting slow above Ottawa East.

Some time ago, I began to facetiously respond to Christine as “Christineaford,” whenever she attempted to jab me with “Robert,” my beloved wife echoing that tried-and-true way of using proper names as warning. This is why full names exist: so one’s parent or spouse can let you know that they’re serious. The dread of hearing my full name, across my mother’s growl. Pavlov, indeed. This morning, attempting to corral children towards breakfast, dressed and prepped for school, I chant a sing-song “Rosebert” and “Aoifebert,” which sparks me to wonder at the possibility that the name “Bert” might have originated as suffix. Is this possible? Ernie, meet auxiliary; a Sesame Street afterthought. Ethelbert, Dagobert, Egbert, Gabbert, Gilbert, Herbert, Humbert, Albert, Norbert, Tolbert, Lambert, Colbert. Wikipedia offers that the name-suffix “-bert” is Germanic, with no examples prior to the sixth century, and second only in Medieval use to the suffix “-wolf.” Only a small number of names holding either are still in common use.

The element -berht has the meaning of “bright,” Old English beorht/berht, Old High German beraht/bereht, ultimately from a Common Germanic *berhtaz, from a PIE root *bhereg- “white, bright.” The female hypocoristic of names containing the same element is Berta.

Modern English bright itself has the same etymology, but it has suffered metathesis at an early date, already in the Old English period, attested as early as AD 700 in the Lindisfarne Gospels. The unmetathesized form disappears after AD 1000 and Middle English from about 1200 has briht universally.

Wikipedia speaks of origins from the pre-Christian goddess Perchta, or Berchta, held by the Upper German, Austrian and Slovenian regions of the Alps, with a suggestion her name, “the bright one” or “the bearer” from the Old High German beraht or bereht from Proto-Germanic berhtaz, possibly related to the name Berchtentag, meaning “Feast of the Epiphany.” Perchta, known as the ‘guardian of the beasts,’ where she oversaw spinning; a god of forming yarn from fibres, drawn out and twisted, onto a bobbin. It is here, one might say, we spin out a yarn. Furthermore, in December 2020, the writer Tamsyn via professional-mothering.com speaks to Perchta as associated with Krampus, whether to come down from the Alps to terrorize children, or “horrifying stories of how she punishes bad children by slitting open the stomachs and replacing their digestive track with straw, rocks, and sometimes trash.”

Tamsyn speaks of Perchta’s association with the wild hunt, with a ghostly procession of scary demons, offering similarities and potential connections to Grimm’s Frau Holle and Mother Goose, and Norse mythology’s Frigg, another goddess of spinning and the wild hunt. How far away from this are Bert’s collection of paper clips, or fondness for pigeons?

Rose, as part of The Girls Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, who sang last week “A Ceremony of Carols op. 28” (1942) and “Saint Nicolas op. 42” (1948) by English composer, conductor and pianist Benjamin Britten (1913-1976). She was amused by the language, and has a solid memory. The time it took us to discover she had a learning disability, unaware of her dyslexia as she’d memorized the books we’d read to her, only pretending to read. All the drive home from the performance, Rose in the backseat, singing out Latin and Middle English lyrics.

The dyslexic must exercise greater intelligence to cope