the green notebook,

, last summer: reflecting on Stuart Ross, Mahaila Smith, Barbara Guest + the above/ground press anniversary reading,

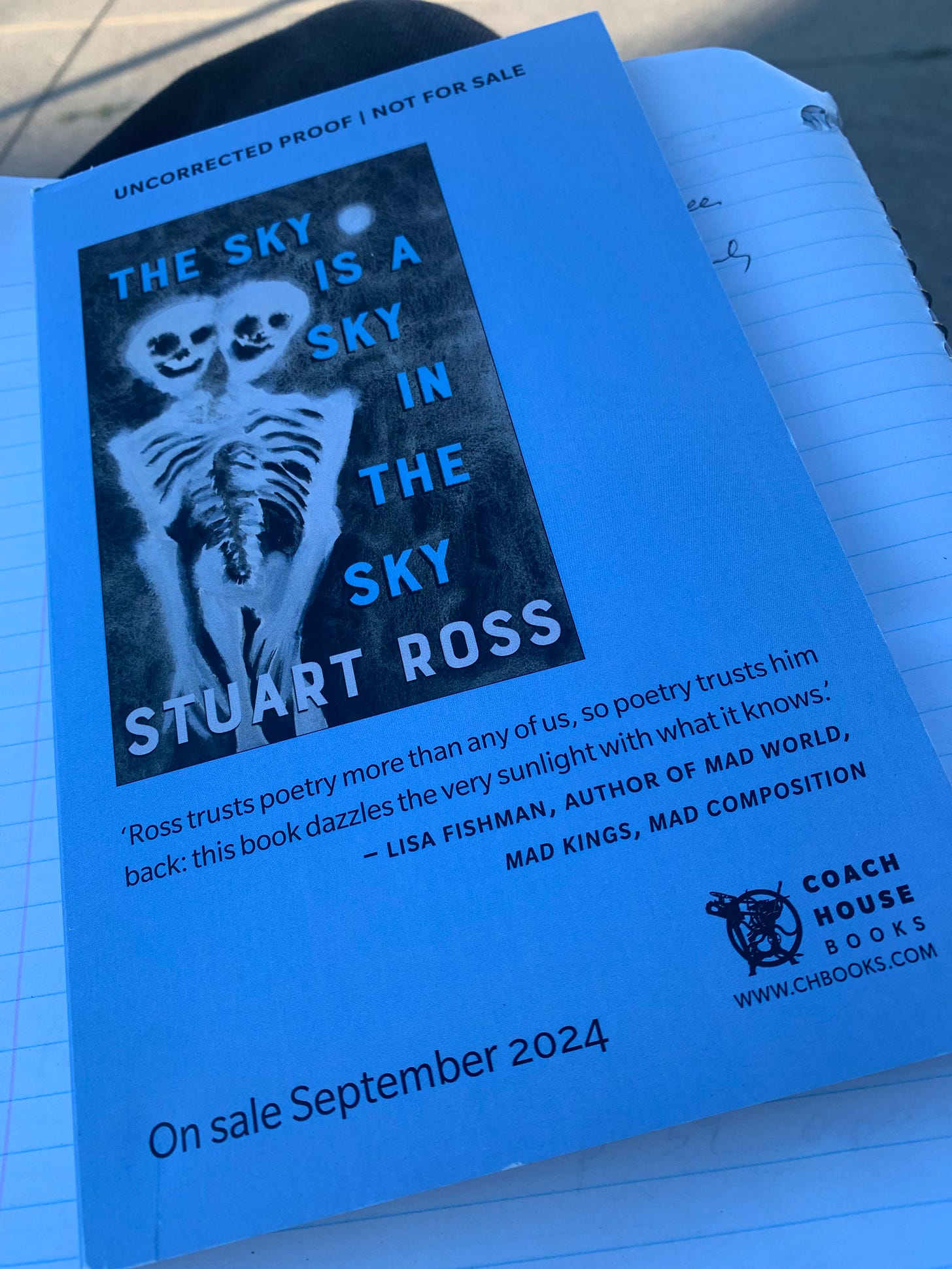

I’m reading through the uncorrected softbound proofs of Cobourg poet, editor, fiction writer and publisher Stuart Ross’ The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky (2024), a poetry collection not officially out for another month or so [note: I’ve reviewed it since then, here]. “The sky’s the limit in these funny and sad head-in-the-clouds poems,” the back cover offers. Ross is housesitting for Ottawa poet D.S. Stymeist and his family this week, some three or four streets north of us, although I haven’t yet seen him in the neighbourhood. I flip his uncorrected pages by the community pool at the back of the RA Centre, as our young ladies attend another round of swimming lessons. The lush green trees against a serious blue.

I wish I’d been more ambitious with housesitting. I have a recollection of apartment-sitting circa 1997 or so for Michael Dennis, ten days of writing at his desk and exploring his library, back when he lived in that infamous apartment space above Wallacks, at Bank and Lisgar Streets. He and Kirsty were on a cycling trip, all the way to Quebec City. I had to keep the west-facing third-storey windows in his office and living room closed despite the heat, otherwise the Bank Street wind tunnel would fill the apartment with dust. I spent a month apartment-sitting for jwcurry and wandering his archive, working at his desk in his Somerset Street West space during the summer of 2003. I kept his sea horses alive, and made sure his bicycle wasn’t stolen (both fell apart within days of him landing home). I worked his gestetner (with permission), and produced small items by Montreal poet Sue Elmslie, and Ottawa poet Seymour Mayne. I housesat for Stephen Brockwell near Beechwood Avenue, in the Lindenlea neighbourhood, circa November 2010, composing the first third of what became If suppose we are a fragment (2014), playing a particular domestic I hadn’t enjoyed in too many years. I invited Christine along for that housesit, as we each had apartments no larger than postage stamps. Our shared space at Stephen’s allowed us a house to co-exist in, easily increasing our comfort levels with each other. We found an apartment together not long after that.

With his amount of housesits over the years, I find it curious as to why Ross hasn’t composed more poems referencing different geographies, personal library visits or housesitting stays. His poems, as well as his fiction, do little in a straightforward manner, coming at any subject or conversation from unexpected angles, although I’m sure he could point me to at least one or two references to Michael Dennis’ library (including one in this collection, I realize). Sideways, as Gillian Wigmore’s blurb on the back cover declares. Perhaps I come at everything too straight: a direct line as my title, and then poems or fictions that outline and twirl across and around my declared, deferred subject. However indirect, still straight. Stuart Ross, from these uncorrected proofs: “I thought I might never walk again. / Nothing about this speaks of love.”

Or, my poems centred around where Stephen Brockwell was living, two houses back, writing: “heritage of undefined, / in special projects / , folder focus evidence a folding, in // or cut up, carve, disjunct, divorce, a parting / , severance, // collectible, proliferate; she recommends / , you punch out stars [.]”

One should never work a final review from advance, uncorrected proofs. From Ross’ own words: “I am stuck in the mirror of my own awareness.”

*

The other night, I organized and hosted a reading and chapbook launch celebrating thirty-one years of above/ground press: six poets, six single-author poetry chapbooks. If we don’t celebrate ourselves, after all, who might we expect would do so? Esquire gets this. This is literature, where celebration rarely happens without some kind of prompt (or a death; but not always then, either). I would hope that the fiftieth anniversary of Stuart Ross’ chapbook press, Proper Tales, only a few short years away, has some resounding fireworks.

“Stilted bones for your birthday / are an expected guest,” read Ottawa poet Mahaila Smith, to launch their Enter the Hyperreal (2024), “present in the evening decanter / poured between me, / the mist and my sister.” The poem this opens, “Put on your shoes or else you need to leave,” includes the citation “after Barbara Guest,” which provides an interesting bonus element to the piece. The late American poet Barbara Guest (1920-2006) was one of those central poets involved in the New York School, important as a mentor to and influence upon multiple generations of poets. I haven’t read nearly enough of Guest’s work, but a collected sits prominently on our poetry shelves, along the dining room side. Word is that Norma Cole is currently co-editing, as she herself recently wrote in an email, “with a lad named Joe Shafer,” a new Barbara Guest selected poems. I’m curious as to the framing their collection might hold, beyond any potential new introduction. Until then, I have The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest (2008), edited by Hadley Haden-Guest, Barbara’s daughter. As Peter Gizzi wrote in his introduction to the collection: “Guest’s poetry, like all great art, makes us reconsider tradition—not as a fixed canonical body that exists behind us or bears us up but as something we move toward. We find it reading back through those very works that were ahead of their own time, their readers, and even their authors—in the poems of Emily Dickinson or William Carlos Williams, for instance.” In a short piece on their chapbook, posted online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, Mahaila Smith writes:

Simulacra like this are fundamental to Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality, which describes the state of our world where we drown in media but lack true information, and live in a place where the concept of “real” no longer exists.

Baudrillard’s theories of simulacra and the hyperreal have inspired me to write. As I was reading his work, I did something that Baudrillard would likely disapprove of, and wrote surreal, dissociative poems based on my lived reality. Enter the Hyperreal is an accumulation of those poems, written over the past four years.

Online, I find a 2003 essay by Guest, “A Reason for Poetics,” that opens with the sentence “The poem begins in silence.” At the other end of the three page piece: “To keep the poem alive after its many varnishings.” I’ll let you imagine, or even look up, the rest.