the green notebook

, reading Charles Bernstein, and Helen Humphreys on Sylvia Plath,

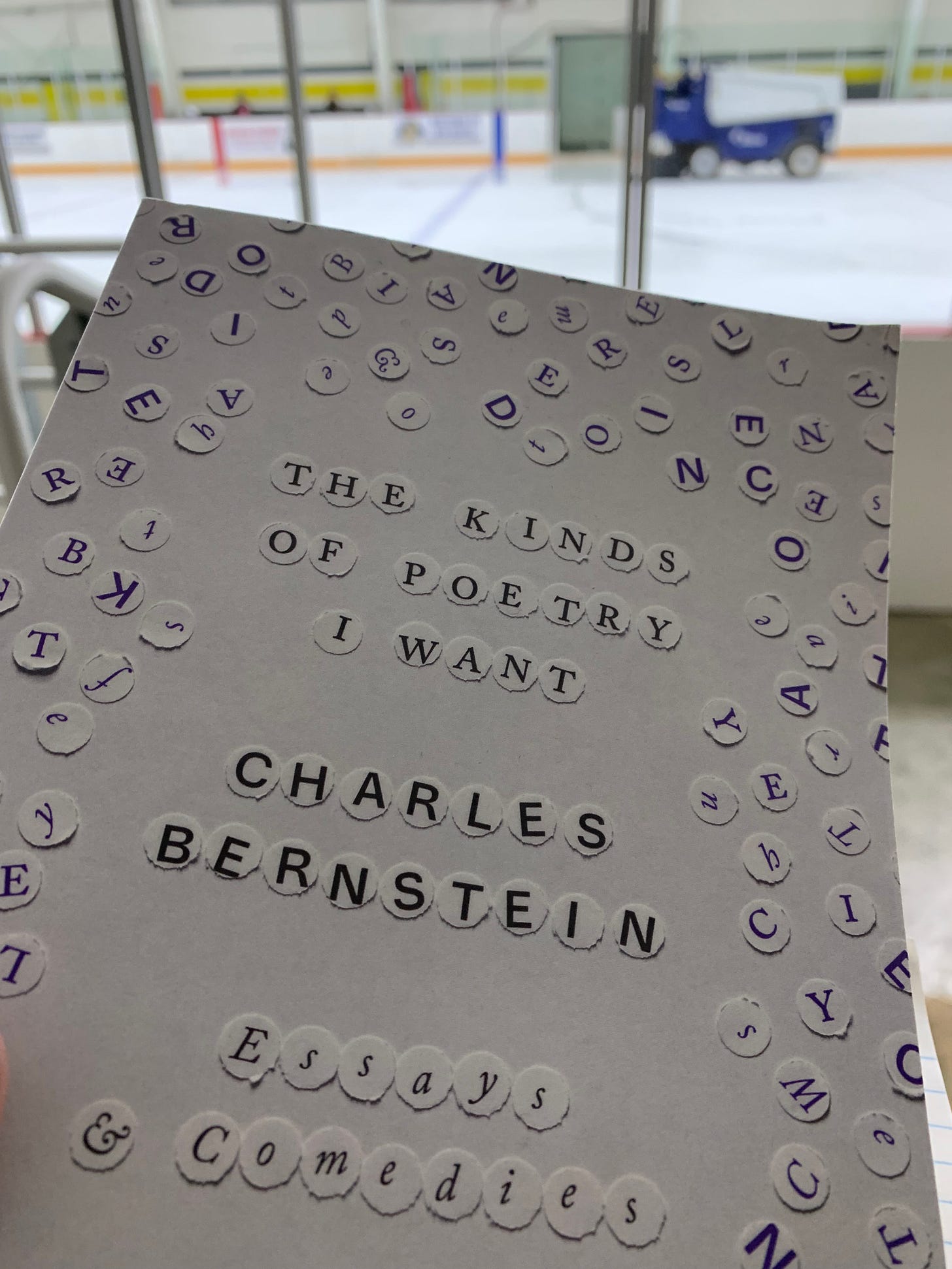

I first encountered the work of American poet and critic Charles Bernstein in the mid-1990s, through his chapbook The Subject (1995), a title I still have, although I’m not entirely sure where. Bernstein has long been an important participant through language poetics, from back when referring to L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry or poets meant exclusively those who had been part of the journal itself: the thirteen issues of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, edited by Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews, from February 1978 to October 1981. Since then, one could say that the term has expanded, even exploded, akin to a Big Bang of North American poetics; the density and force of that single moment so great that it burst, influencing generations of poets and critics across the years since.

“Art’s not fair.” he writes, early on in the collection. “People we’d like to be the best, who deserve to be, are, often as not, not. The worst produce some of the best, nor is their cruelty compensated for by their great art, which exacerbates the quandary, casting a thrilling, demonic light on their achievements.” These are the sorts of conversations many have been wrestling with lately, in regards to the works of Alice Munro, and of Neil Gaiman, and of whomever else. Does one jettison the work and the author entirely, or read within a different context? Some might suggest the Gaiman accusations make him easier to outright refuse, but his projects are still current, still so tied into the culture. Dark Horse Comics, for example, have dropped him entirely, cancelling a plethora of collaborative projects and reissues. There are no easy answers, and no single answer that might satisfy every individual.

Today is Inauguration Day in the United States. Today is Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Blue Monday, folly. How did we get here.

*

Further to Helen Humphreys: I am intrigued at how she sought to connect to elements of Sylvia Plath’s writing path. She writes of discovering and devouring Plath’s work prior to her year in England, to deliberately follow Plath’s lead through a residency at the arts colony Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York. From the Yaddo website, I discover an article in their fall 2015 newsletter, “The Leap: Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath and a Mesmerizing Season,” that speaks of that particular moment in the autumn of 1959: “Hughes worked on his second book of poetry, Lupercal, and an oratorio based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, while Plath dug in on a large number of new poems that were ultimately collected in her first book, The Colossus and Other Poems.” During her residency, Humphreys even achieved the same room as Sylvia Plath, as described through Plath’s journals. “She described her writer’s studio in detail,” Humphreys writes, “and I was thrilled to discover that nothing had changed in that room from her time to mine. The furniture was not only the same furniture but was positioned where it had always been—wooden table by the window, single iron bedstead against the sloping attic wall.”

We follow the examples of writers we admire, hoping something of their talent, their influence, their energies, might provide us some twinkling of the same. An example of someone who made it, to offset the isolations. To provide us with hope. My early twenties, circa 1993, as I sat afternoons at the Royal Oak Pub at Ottawa’s Bank and Gilmour, drinking pints of Toby and attempting poems, as Michael Dennis’ poems, through his poems for jessica-flynn (1986), described doing the same. Ralph Connor, who wrote tales from Glengarry County nearly a century before I arrived along those same concession roads, the lone creative artist in a landscape otherwise indifferent. Elizabeth Smart, who emerged from a socially-conservative Ottawa to explore the lyric, exploding beyond boundaries that could never contain her. From these, my own.

Through a blend of circumstance and planning, Humphreys followed Plath’s example, down to the same room, the same writing-desk. The long shadow of Sylvia Plath, one I’ve never personally held, although I went through my own period of reading the work. The example I continue to return to is Elizabeth Smart, the one who never imagined not having children, and who wrote through, and even because of, those years as best as she could, emerging out the other end with journals, poems, stories and a novel as infamous as the story that birthed it.

To attend the work but not fall too deep into ourselves, allowing a space in the world.

It is snowing in New Orleans today.

Yes to Elizabeth S~!

Thank you. Interesting thoughts here.