the green notebook,

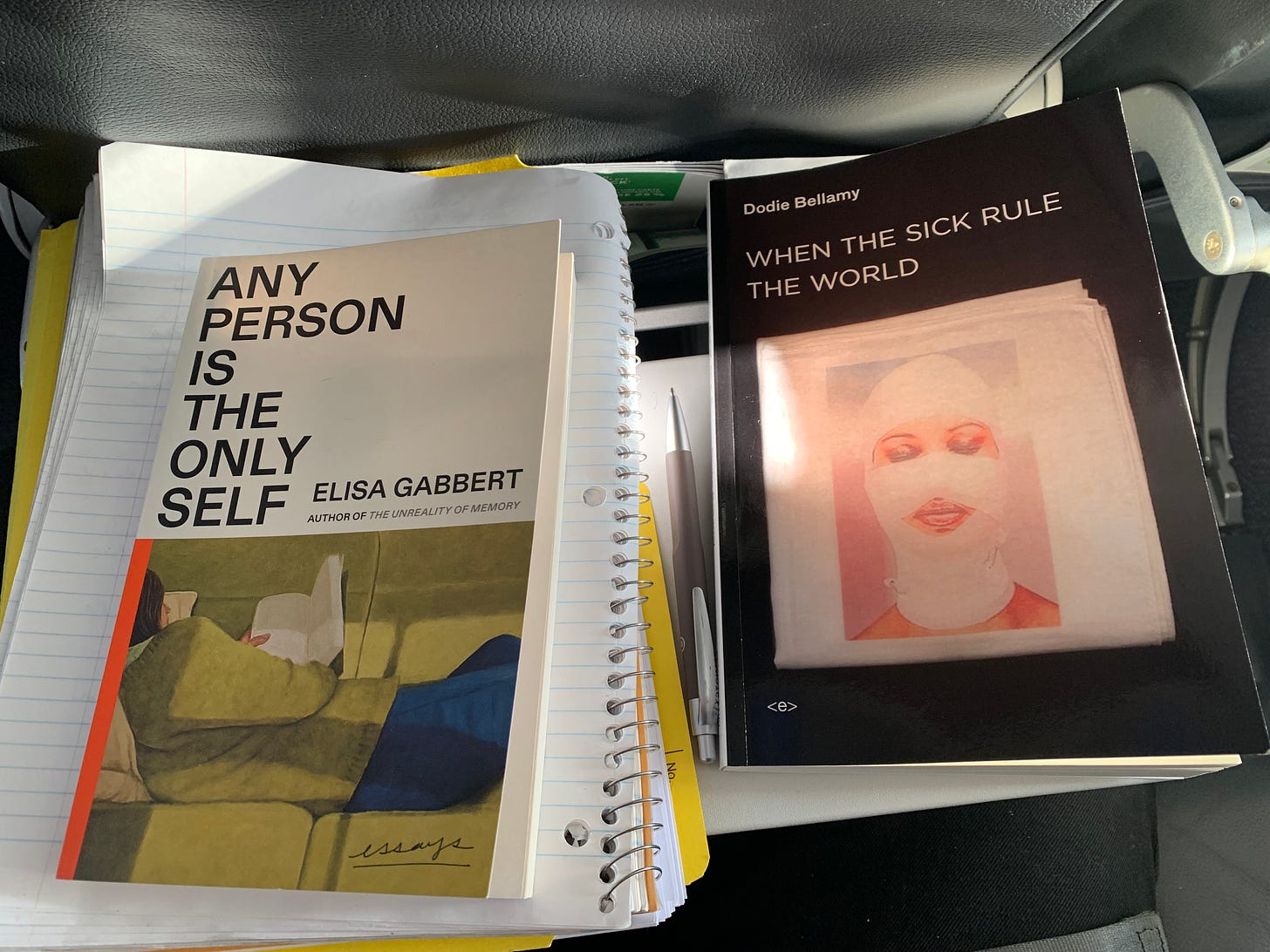

, reading Dodie Bellamy on the plane back from Calgary,

“The essay is a form I’ve always found oppressive,” wrote Dodie Bellamy in her “BARF MANIFESTO” a wildly brilliant essay included in her When the Sick Rule the World (2015), “a form so conservative it begs to be dismantled. In the San Francisco avant garde feminist poetic circle of the early ‘80s, a sort of patchwork personal essay was de rigueur. The feminist poetic essay was riddled with collaged texts and vulnerability. It switched person at will, ‘I’ flipping to ‘she,’ inside magically flipping to outside, and back again. I don’t know what to make of all these anti-logocentric Theresa Cha/Cixious/Irigaray inspired poetic prose things, spastically shifting and disrupting before my eyes with no apparent rhyme or reason.” Found amongst the shelves of Calgary’s Shelf Life Books, this is the first work of Bellamy I’ve picked up, properly sat down and read, the four of us flying home from our western adventures. I’ve spent years holding Bellamy on an unwritten list of authors I should be reading, a floating list that would also include Jenny Boully, W.G. Sebald, Miriam Toews, Hazel Jane Plante and Jessica Johns, among others. There is so much to get to.

Held together as a “moving meld of essay, memoir, and story,” Bellamy’s prose through When the Sick Rule the World is an assemblage of messy precision and expansiveness, and I’m very much enjoying the inquisitive fearlessness of her observations, admissions and critiques, achieving moments and comprehensions a more timid writer could never.

I’ve known of her work for years, through my interactions with, and with the work of her husband, the late San Francisco poet, author, editor and playwright Kevin Killian (1952-2019), who was always such a delight to interact with, even if our years’ of correspondence were purely through email and post, and never in person. If you haven’t seen it, I would recommend the anthology they co-edited, Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997 (2017), a collection offering a spotlight on an array of compelling and daring experimental prose.

To properly skewer a form, one must first understand it, and I might say I’m still learning, although one would hope that one is always and ever learning, evolving, as one moves through the world, and through writing. As I might work through an idea. It isn’t that I have so much to say, per se, certainly. To begin to repeat myself, myself. What new perspective might my own inquires offer, if even to me? Further along in the same essay, as Bellamy writes:

I used to write reviews pretty regularly for the San Francisco Chronicle, and even though my editor Oscar Villalon was a joy to work with, the form was killing me, the suppression of the self, the tidiness, the pretense of objectivity. Perception is about framing; when it comes to doling out opinions, I am the frame. To deny that framing feels so—I don’t know—dishonest. I have a similar problem with attitudes that some students in fiction workshops have absorbed, the ideology that fiction is supposed to be fictive, that fiction isn’t about me, and that’s a good thing because I’m the god of this made up world, and the further I can push characters and plot away from my own personality and experiences, the greater the writer I am. I always want to say put some of yourself in there and maybe you can pump some life into this stuff—but I don’t because I know me being brutal and cranky won’t help anybody.

Two seas ahead and across the aisle, a gentleman is playing Angry Birds on the seat console. As I watch him progress levels, I struggle to understand the point of this particular game. I might never understand.

*

On our flight en route home, I briefly watch as Rose draws, with her finger, thick black lines on her laptop screen. Across the aisle from my own aisle seat, watching her zoom in, zoom out. She is four days into eleven years old. She is hard at work.

The Air Canada console suggests we are now entering Ontario, by Sand Lake, Aulneau Peninsula, Big Island.

*

As part of the same essay, Dodie Bellamy writes that “Kevin [Killiam] wrote a play for Tariq’s 40th birthday—it was called ‘Tariq Alvi’s Nightmare’—we performed the play at Tariq’s birthday party in Lee and Erik’s backyard in the hills above the Castro.” She mentions Killian writing and they performing it, but the only image in my head of “performing a play we wrote” include a person wildly tossing hands up in the air while monologuing, and I know that can’t be right. There’s a part of me now that wonders if I’m too simple to know what a play is. I know what a play is. But clearly I haven’t seen enough, or enough good ones, to have an image or recollection to pull up beyond the cartoonishly ridiculous.

*

Vigil, as in attention. Attend. A subtitle I incorporated from the late C.D. Wright, although mine neither specifically poetry nor focused upon or within a particular geography. Moving around and through genre, borders. Writing, which is also reading. Neither specifically American nor Canadian in material focus, but Canadian in approach, as that is who I have ever been. One shifts in perspective from experience, certainly, but foundations take far more. A boy from County Glen, perhaps all that I’ve ever been. Comfortably so. And so, go forth.

Our plane lands in Ottawa. My shoe is untied.