the green notebook

Sainte-Adèle, reading Maggie Nelson, Eileen Myles, Melanie Siebert, James Ephraim McGirt, + my collaboration with Christine,

September 1, Sainte-Adèle, Quebec. The Laurentides. The rain is pounding on the roof, the deck.

Christine and I have both composed poems on and around this space, this place. we’ve an unfinished, untitled collaborative project, one we’ve barely touched since she was pregnant with Rose. I haven’t yet given up on the idea. We’re probably half-through a full-length manuscript, responding to each other’s poems in a call-and-response. I would write three poems and Christine composed three in response, as I would compose two or three in return, etcetera. We attended the language of the space, and the counterpoint of my unilingual self newly introduced to this geography against her perspective as a French-speaker in these Laurentides, from a family space she’s known since youth. From the poem “mantle,” as Christine wrote:

August stings, deceives, unravels. Under my feet the lawn corporeals, slides up and slips. It circles round and there are trees and they are around and the windshudders. The trees shudderflex. The rain bends the roof. Barely bearable, instep peels down onto cold grass moves imperceptibly. The deck sighs. My feet are on the grass. We labyrinth round. My buried dogs yip in the earth. They eye you cautiously. The deer eat the flowers. The rain buckets.

In an interview on collaboration American poet and publisher Jen Tynes conducted with the two of us for Horse Less Press back in 2015, Christine responded: “rob mentions it in his reply but it’s been an odd collaboration for me in part because it treads into private/familial/dream space of mine. So while he can find some connections to family history of his own (visits to the Laurentians by his grandparents for example) and in the historic presence of the place – all of my connections to the cottage and the town are childhood bred. As such they’re somewhat sacrosanct and instinctual. When I was young I felt a definitive pull to the elemental aspects of the cottage. The thunderstorms that almost shake the house. The number of stars visible at night. All of which seemed wild and perfect to my little suburban head, even if it was completely tame and cozy. It was a retreat for me. So to collaborate with rob in this project feels a little strange because it contextualizes my own psychic dream space into something more detached.”

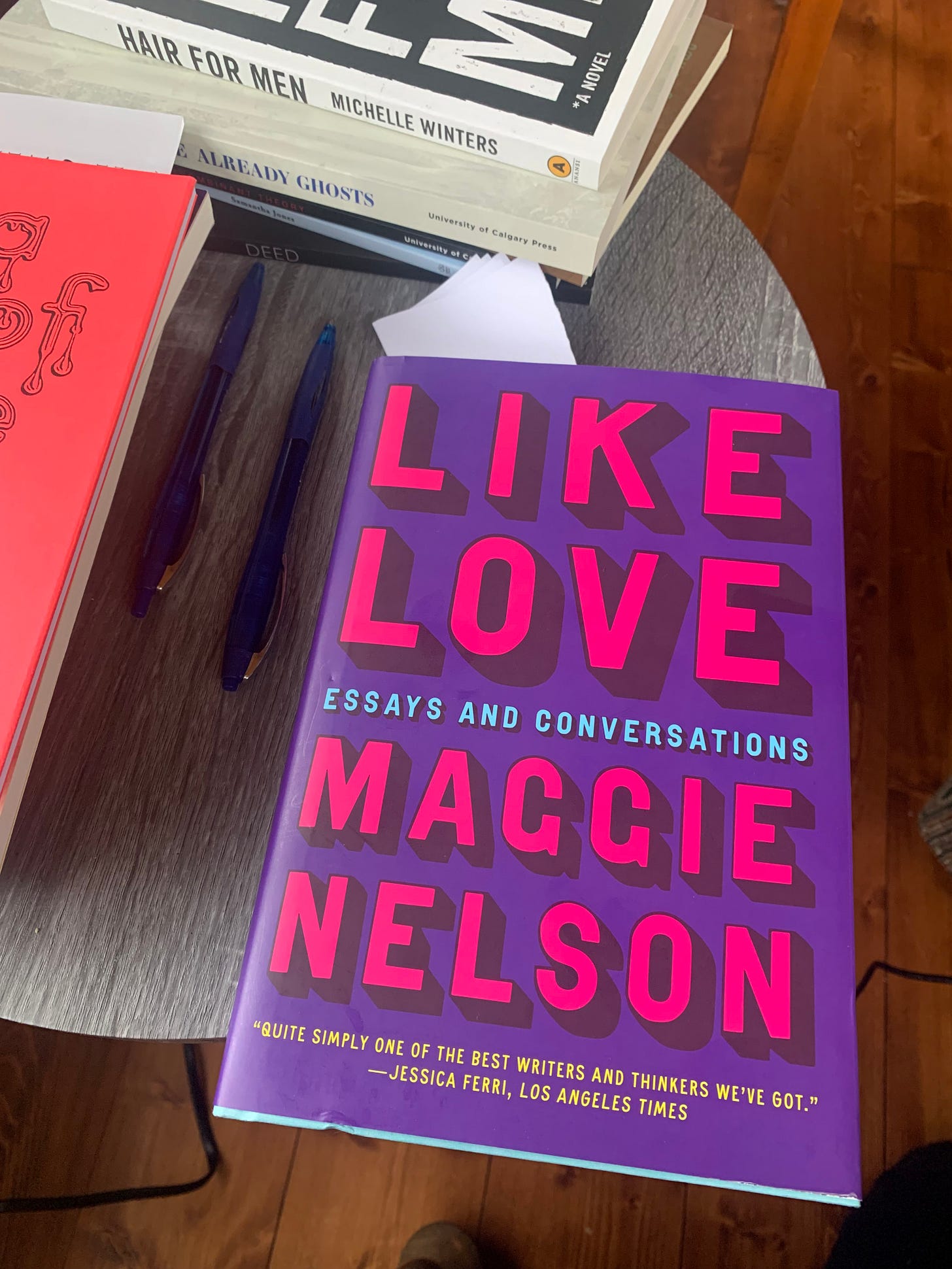

Further through Maggie Nelson’s Like Love: Essays and Conversations (2024), I catch an interview she conducted with Eileen Myles, originally for a special issue on Myles’ work for Women’s Studies: An Inter-Disciplinary Journal, in which they discuss “the activist campaign in which Myles has been involved to save Manhattan’s East River Park—along with its 991 trees—from demolition.” As Myles responds: “And a park is one of the many studios of the writer. For me that’s always been one of the puzzles about what we are and what we do. What is that place? It does and it doesn’t exist, because it’s language, but it camps out in the world in all these various places, and there are some places that are more conducive to that camping out that others.”

*

I’ve been invited to read in Picton later this month, to accompany Christine at her event. Childcare is secured, travel is secured. A day we’ll drive to Picton once the young ladies in school to read that night, as Christine trains home the following morning and I continue west. I’ll be participating in a small press fair that weekend as part of the Toronto International Festival of Authors, staying in Burlington with poet Andy Weaver.

On the drive north, into these hills: heavy rain against the windshield, driving the final stretch east along Highway 50. The fog across the hills, the black corners of brush.

According to my notes, across a Sainte-Adèle Easter long weekend in 2022, I saved a file to my hard-drive with the title “The Museum of Practical Things,” meant as a place-holder title for an eventual potential collection of prose poems. Strange to think this was two and a half years ago from where I’m now sitting, in that same cottage sunroom, and I’ve composed and completed not a single poem. I had originally imagined this as a collection of self-contained prose poems on objects, each half a page or more, but I haven’t quite reached the attention required to begin. Given I was in the midst of other projects, I set the title aside, for later thinking.

And yet, over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been gathering titles I’m slipping into the same Word document, including “Light studies on the Ottawa River,” and “Five conversations with _____.” I don’t know if this means the poems might be closer to composition, but I can feel that itch growing. I can feel that sense of the poem, the fragment, pushing to reveal itself.

Labour Day weekend at the cottage, where Facebook memories claims we were also, twelve years earlier. A photograph of those same trees, well before Aoife, or Rose. A few weeks prior to our wedding. A weekend away, and a heft of reading. So far on this particular jaunt, I’ve been sketching out notes on poetry titles by Melanie Siebert, Mona Fertig, Oluwaseun Olayiwola, Keagan Hawthorne, Aditi Machado, Nat Raha and Amy De’Ath, as well as Maggie Nelson’s collection of essays and interviews. Our final morning, the sun, the deer. From Melanie Siebert’s Signal Infinities (2024): “You expand unfixably in the crucial last seconds.”

This morning, the Academy of American Poets posts the poem “Nothing To Do” by North Carolina poet James Ephraim McGirt (1874-1930) to social media: “The fields are white, / The laborers are few; / Yet say the idle, / There’s nothing to do.”

Or, as my friend Patrick Gant posts to Facebook, a quote from Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), one I’m unable to source, although the internet provides with an array of opportunities to purchase mugs or other keepsakes with same:

And all at once, Summer collapsed into Fall.