the green notebook

, reading Gail Simone, Hebe Uhart, Eileen Myles, Devon Price + Julie Carr,

American writer of comics and animation, the brilliant Gail Simone, offers a new tweet-thread describing her first experience, years ago, of attending a comic convention. If you don’t know anything about her work, it is thanks to her we enjoy Deadpool movies, for example (it was she who really fleshed out the character), and she’s currently working on a new run of Uncanny X-Men. She hadn’t even been to a convention as an audience member, she begins, and it was only upon landing did she discover that her solo panel was labelled “Gail Simone tells you how to write comics.” She knew what she was doing, but hadn’t articulated the process aloud, so didn’t know how to approach it. Through the process of speaking (and fumbling/rambling, as she suggested), her take-away was that it was important for any creator to not give away their secrets, to “protect their tool-box,” although I think this was more valuable:

It was that I had taught MYSELF the answers to those questions, non-verbally. I’m still doing that.

I would say that this is the take-away, and not her suggestion of protection. Any creator can provide the tools of how they create, but not every tool works for every practitioner.

There’s little point in hoarding tools, I say. Give it all away.

*

Online at Washington Independent Review of Books, Karl Straub reviews A Question of Belonging: Crónicas (2024) by Argentine writer Hebe Uhart (1936-2018), translated by Anna Vilner. I suspect I might actually have to start looking up some of these works of crónicas, and see how they might relate to some of these other structures, whether the day book, the literary journal, or whatever this is that I’m doing. As Straub writes on her work:

Her typical method was to travel to a place — usually a small town in South America — where she’d never been. She relied on various insiders to guide her toward knowledgeable locals, but these recommendations often failed to pan out, forcing her to fall back on her instincts. She would then install herself at a coffeeshop, a bookstore, or another convivial high-traffic area, where she could meet people and suss out her next move. Occasionally, despite all her preparation and savvy, the fix would be in and nobody would talk to her. At this point, the circled-wagons phenomenon would become the story.

Fall back on her instincts, he writes. Akin to the Fred Wah notion of the “drunken tai chi,” the old master deliberately throwing off his own balance, and forcing his instincts to take over. When developing a skill, one begins the to learn the importance of trusting one’s own judgement.

*

Reading through James Yeh’s stunning interview with legendary American poet Eileen Myles in the latest issue of The Believer (Vol. 21, No. 2; Summer 2024), my eye is briefly distracted toward the fifth part of a “microinterview” with Devon Price, conducted by Emerson Whitney. I’m struck by how Price, an American social psychologist, blogger and author focusing on autism, speaks to how community is so often approached in the wrong direction. “Your approach is often colonialist, if that’s all you’ve ever known.” The mistake, as Price articulates, of asking yourself what you can take instead of what you can bring. I am startled by both the wisdom and obviousness of their statement. How the rest of us, perhaps, have approached the whole consideration of community entirely wrong. Community as a kind of pot-luck, further enriched by each succeeding participant.

The interview with Eileen Myles is incredibly rich, offering their own knowledge based on skill, experience, and too much to repeat here, but one that echoes some of Gail Simone’s thinking:

I just think it’s repetition. It’s like anything. It’s really similar to how you know if a poem is good. You know because you’ve just been there and you’ve been repeating and repeating. For some reason lately I’m freaky on repetition as a value. Because everything that’s good, you’ve done it again and again and again and it becomes your friend and it becomes your turf and it becomes your nest and then it’s just the right place to be and the right way to be.

Anyone interested in writing process and structure, or even the very notion of how to keep going, should read through this interview. How to not only figure out how best to write but how best you should be writing. This is, after all, an important distinction, and one not everyone seems to have figured out. It took me close to a decade of active prose writing before I came to that same conclusion: not how I thought a novel should be written, but how best to write a novel in my own way. Give out all your tools, I say. A bit further on in the same answer, as Myles offers:

You kind of make your own nest, that’s the thing.

*

I’m having a hard time focusing on much of anything today, knowing my short story collection, On Beauty, lands today on our doorstep, direct from the printer. I’ve already addressed a handful of envelopes to mail copies immediately out, including for Patreon supporters and a handful of my half-siblings. Our young ladies enjoy the first day of their week-long day camp at the Aviation Museum, which means I’m only here for another few hours. The Purolator website says “OTTAWA: On vehicle for delivery.” This has remained unchanged since 8:22am. I know, because I keep checking it.

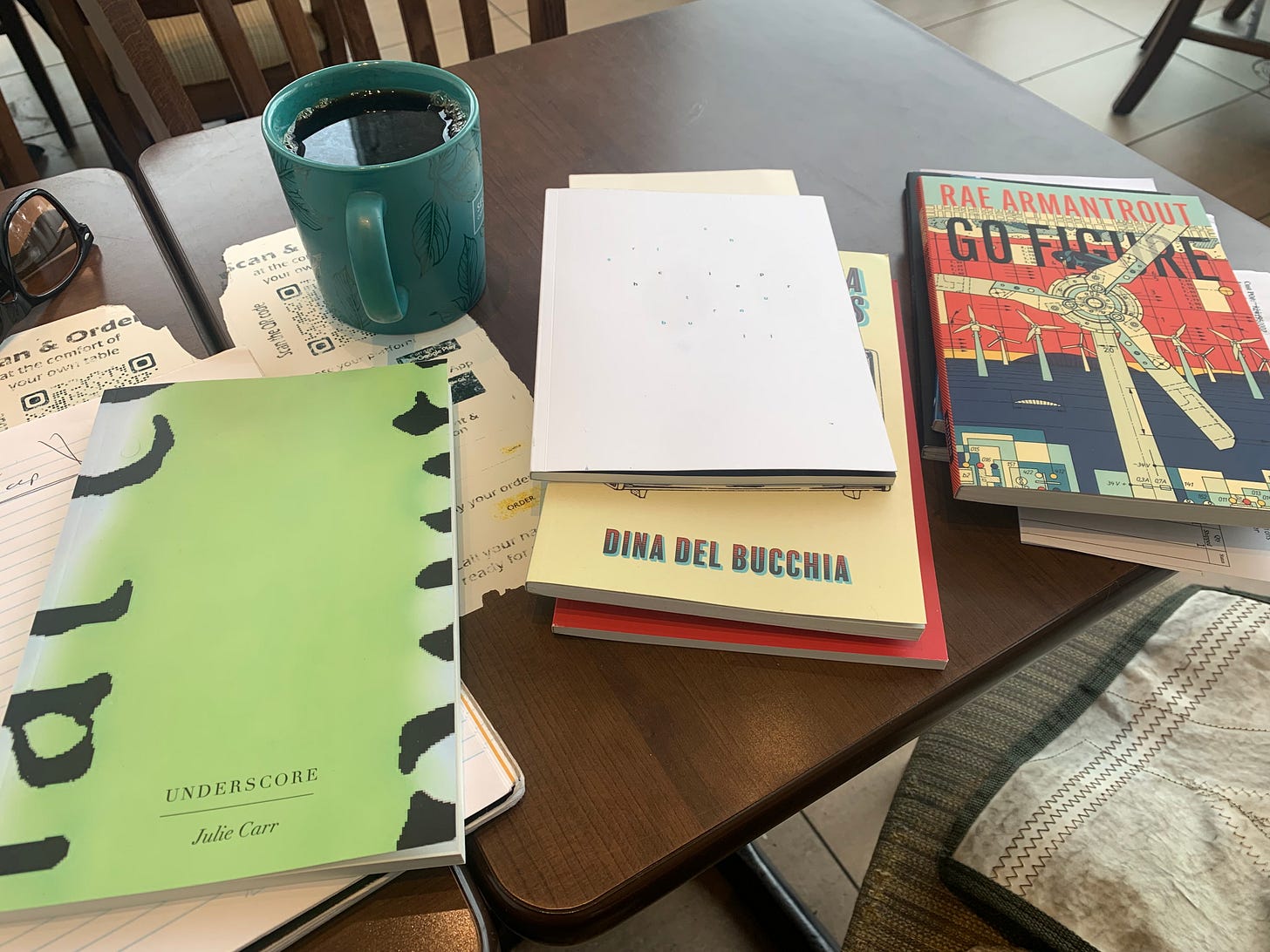

I am attempting to work on reviews of the new Stuart Ross, of the new Rae Armantrout. Every bump from the yard brings me back to the door, and to silence. I can’t hold a thought.

Julie Carr, from UNDERSCORE (2024): “When someone dies, said Ben, we redraw our map of the world.”