the green notebook,

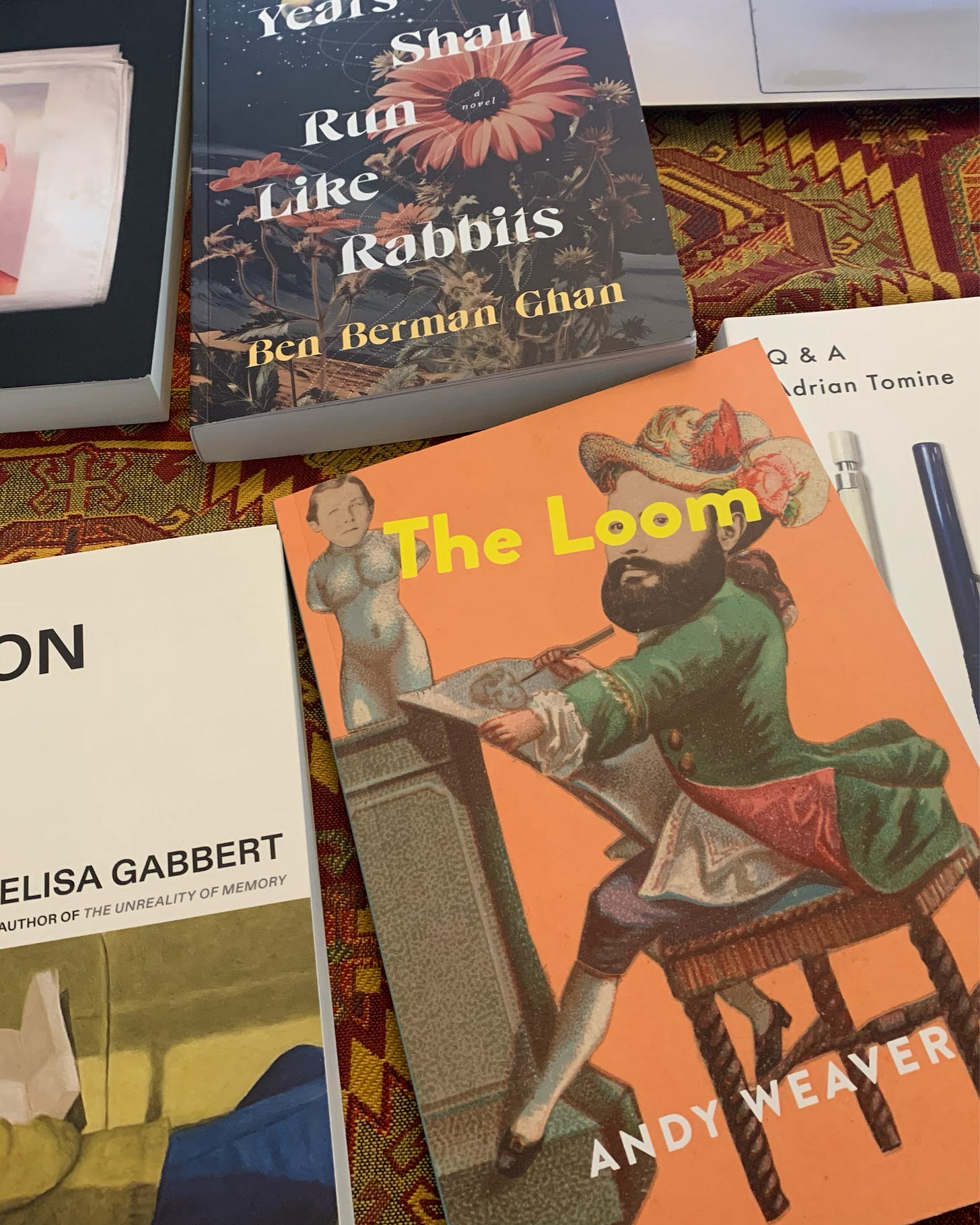

, reading Adrian Tomine, Elisa Gabbert, ryan fitzpatrick + Monty Reid in Calgary,

I’m really enjoying American cartoonist Adrian Tomine’s new Q & A (2024), a book-length extension of the letters page he used to have at the back of issues of his irregular (originally self-published) Optic Nerve (1991-2015), answering questions he received from readers. There’s an attention he has to craft that I quite like, providing a glimpse into what is clearly a deeply thoughtful process on his part. As part of these responses, he offers: “You might be wondering why, in the 21st century, am I still drawing on paper? The simplest explanation is that I enjoy working with pens and pencils and paper, and for whatever reason, I find working on a computer to be a physically-taxing, eyeball-straining chore.”

I’ve written elsewhere my appreciation for the descriptions of process by of other artists, whether the conversations with actors and directors as part of Inside the Actors Studio (I was crestfallen when Bravo took that off the air in Canada, as I found many of those conversations enlightening), or the nearly eight hours of Peter Jackson’s documentary series, The Beatles: Get Back (2021). There’s enormous overlap to hearing actors or musicians or cartoonists or writers talk about process, less distant from each other than perhaps we pretend. And, as Tomine, how I prefer to begin is through a notebook process of longhand, scribbling across spiral-bound mass market notebooks, whether through an afternoon and/or evening at the pub, a morning in the coffeeshop, or the hours of flying between Calgary and Ottawa, as we’re doing this week. Composing at my machine only takes me so far, at least generatively, although once at my desk, the scribbled notes are entered into my laptop, as I attempt to shape in a coherent way. Sometimes notes need to be stitched or woven together; other times, only minor changes are made between what a moment across a full page of scribbling had already held.

I’ve been a fan of Tomine’s work for some time, having caught 32 Stories (1995) soon after discovering Optic Nerve. Since then, I’ve attempted to pick up everything he’s produced. I appreciate his ability to articulate so much in a few scant lines, packing complex emotion in the space of a gesture, or pacing. I would suspect that his work, whether or not I was aware at the time, easily influenced the way I approach the pacing of my own short stories. Here's what I wrote when I reviewed his Killing and Dying (2015):

Working with multiple narrative styles, Tomine has long had the ability to write his stories with an incredible density, able to encapsulate and articulate multiple levels of silence, discomfort, awkwardness and interpersonal twists in the simplest, most subtle ways. Often, he manages to say an incredible amount even in a sequence of panels with almost no dialogue, harnessing a level of emotion that is multi-leveled, and even contradictory. How are we to feel of a character living with such pain and loss, and even anger, lashing out at his partner? How are we to feel of his partner once he is, out of nowhere, left behind? And why didn’t she, nor we, see such an end long coming? There are times I’m even amazed at how he can take a character down a particular path far enough to understand how it is he arrived, despite the distance. Through writing out characters experiencing and moving through their lives, Tomine manages to capture the essence of how one moves from point a to point b, as we see his characters move through all the extraordinary ordinary things that make up living, and his stories are grounded in such inquiries of: how did I get here? How did we get here? And what do we do from here?

In my mind, the stories of Adrian Tomine are as striking and worthy as anything being composed by Lorrie Moore and Lydia Davis for their brevity, expansiveness and emotional power.

This really is a delightfully open book of insights and a remarkable (and humble, occasionally self-depreciating) clarity, as Tomine answers questions as best as he can, telling stories, describing paper and brushes, and offering his own perspective on a range of topics around and through the scope of his creative life. I was struck by his perspective on writing and family, as he quotes himself from a 2018 interview with The Washington Post, where he responded: “And having kids was like discovering this secret trap door in that corner that allowed me to write differently about new things. It's also just had such a strong impact on me as a person, especially in terms of how I interact with the world, that I think that can’t not show up in the work to some degree.”

His response about dialogue is a bit of a deep cut, as I’ve never felt good at writing dialogue, realizing over the years I work better through tone and gesture, focusing instead on a particular kind of interiority. As Tomine writes: “This might be a bit personal, but my sense is that people who have a hard time writing good dialogue are maybe not the best listeners.”

Ouch, fella. Just ouch.

*

Reading through Denver poet and essayist Elisa Gabbert’s latest collection of essays, Any Person Is the Only Self (2024), I come upon the book-specific term “foxed,” as she writes: “The new arrivals aren’t in any order yet, and the staff buys a lot of books—new books and old books, classics and trash. They’ve often been sold and resold. The pages are often foxed.” Naturally, Christine, the book conservator, is fully aware of this word, but I had to look it up. We are curious as to how Gabbert came upon the term, although I’ve a sequence of words, I’m sure, that might baffle.

As Gabbert responded to my query via email: “I think I heard it first from John? He's a longtime used bookstore freak, probably heard it from making friends with booksellers/buyers. I like it because I like foxes!”

Her essay, “The Stupid Classics Book Club,” writes that their reading group originally began as a joke, but then struck as an actual worthy idea. As she writes: “The project of this book club would be to read all the corny stuff from the canon that we really should have read in school but never had.” She offers examples of books we’ve only experienced through sources secondary or beyond. Has anyone actually read Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), or Moby-Dick: or, The Whale (1851)? How some books are surprisingly good; and others, surprisingly bad. It’s a brilliant idea: books we might only know through culture, whether film adaptations or references on The Simpsons. She continues:

It’s not that these artists don’t get enough attention; it’s more that when something good is widely appreciated, we forget to take it seriously. We don’t think it needs us. Or popularity itself makes art feel like a joke; we assume if it’s famous, it must be obvious.

*

On our final full day in Calgary, we set aside our potential drive to Banff, due to an onslaught of snow. We set aside our backup plan of driving to Drumheller, and their infamous dinosaur museum, for similar reasons. Different roads, the same blanket of snow. The Royal Tyrrel, where Monty Reid spent seventeen years prior to landing in Ottawa at the Museum of Nature in 1999, but I suppose that will have to wait a bit longer. A record-setting snowfall, they say, for November 23 in Calgary. Unofficial reports as high as 25 or 30 centimetres, with the airport receiving 17.8 cm of snowfall, beating the previous high mark of 13.2 cm set in 2018. The car slips, slow, across unplowed quarters, and we make our way to the theatres at CF Chinook Centre, Calgary’s largest shopping mall, where we were taking the young ladies to see the film adaptation of Wicked.

It is curious to realize that the theatre puts us slightly west of Ogden, the Calgary neighbourhood where Canadian poet and critic ryan fitzpatrick originated, and where they first began to explore their lyric critique of capitalism amid the shores of the long poem, the serial poem. From fitzpatrick’s revised notes (2000):

we draw a sword where the rail goes

through the ogden shops

brick blue fathoming a contract line

like the robin in the tree nuzzes money

like sherwood tells stories about coyotes

pull seams with blue teeth

the poet throat cuts

pages in oil barrels under graves bridge

that's what they say

bp in bed with capitalism then BP

blows corporate lips kisses

And then there is Monty Reid himself, from the opening sequence of Disappointment Island (2006), via his “Songs for the Mammoth Steppe,” a poem for the world’s most extensive biodome, a shape that no longer exists:

At the farthest margins of my life

lies the ice of pure simplicity.