I tend to think of my fiction constructions as assembling a quilt, I think, over the notion of collage. My short stories attempt to stitch together sections that form less of an amorphous shape than a logical pattern through the leaps and bounds and connections that might, at first, seem rather tenuous. The arc of the story. Over the past decade, I’ve been focusing more on writing short fiction than poetry, and there is something of the shape of the prose I’ve been working that feels closer to the state of my current thinking, if that makes sense. Somehow, prose has become, even beyond the scope of the poem, the container that can hold anything and everything I might think to include. As Lydia Davis responds via a recent interview in the online journal splonk: “I wanted an approach that would free me up and let me dive quickly into unfamiliar imaginative and emotional territory.” Perhaps it is simply this feeling of freshness of territory, of form, that allows me this flush.

While working the sections of a short story, sometimes a fresh section might offer an alternate perspective, or a leap down the narrative. Other times the connections might be less clear. The goals of revision would include the work of attempting the stitching pattern to be able to bring that section into where it might not immediately fit, until it finally and completely does. Some stories take months to fine-tune, even across but a page or two. Some have taken more than a year. For example, this very short story took a few years to complete, returning repeatedly to find that connector, that hinge, between opening idea (Orhan Pamuk) and closing idea (Sesame Street), until it finally cohered:

From a period that began in the late 1990s, Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk’s writing studio in Istanbul sat in an apartment on Susan Sokak, a street name that translated into English as “Sesame Street.” I doubt this locale was what the Children’s Television Workshop was originally referring to, as Jim Henson’s Muppets wander their fictional fragment of Manhattan. Memory is often glacial, as we know, and accumulates as naturally as it erodes. Ernie and Bert sit on the front step as Oscar the Grouch barks at passers-by, monsters and Muppets and humans alike. Elmo, no longer the new kid, old enough now to have kids of his own. Big Bird, who only managed to correctly remember Mr. Hooper’s name once both actor and character had expired, his long-standing twist of a name that succeeding generations of children would most likely never be aware of.

Here is a section I sketched out the other day, still rather rough. I was thinking of it in terms of a story-in-progress, “Our Lady of the Broken Windows,” but I’m not entirely sure yet how it might fit, if at all. Perhaps this might be something to file away for another piece.

The narrative of medieval paintings is very different than those of what developed later, across the trajectory of western art. These pieces are meant to tell stories, occasionally depicting the same character multiple times across the same piece, as though you are to read the story across from one image to the next. Medieval paintings also suggest earlier versions of footwear prompted a different kind of step: toe-heel, instead of the contemporary heel-toe. Why, my daughter asks, less a question than a statement of judgement, are they standing so weird. Toes forever pointed toward whatever direction the mind sees, aims toward, as the rest of the body follows.

*

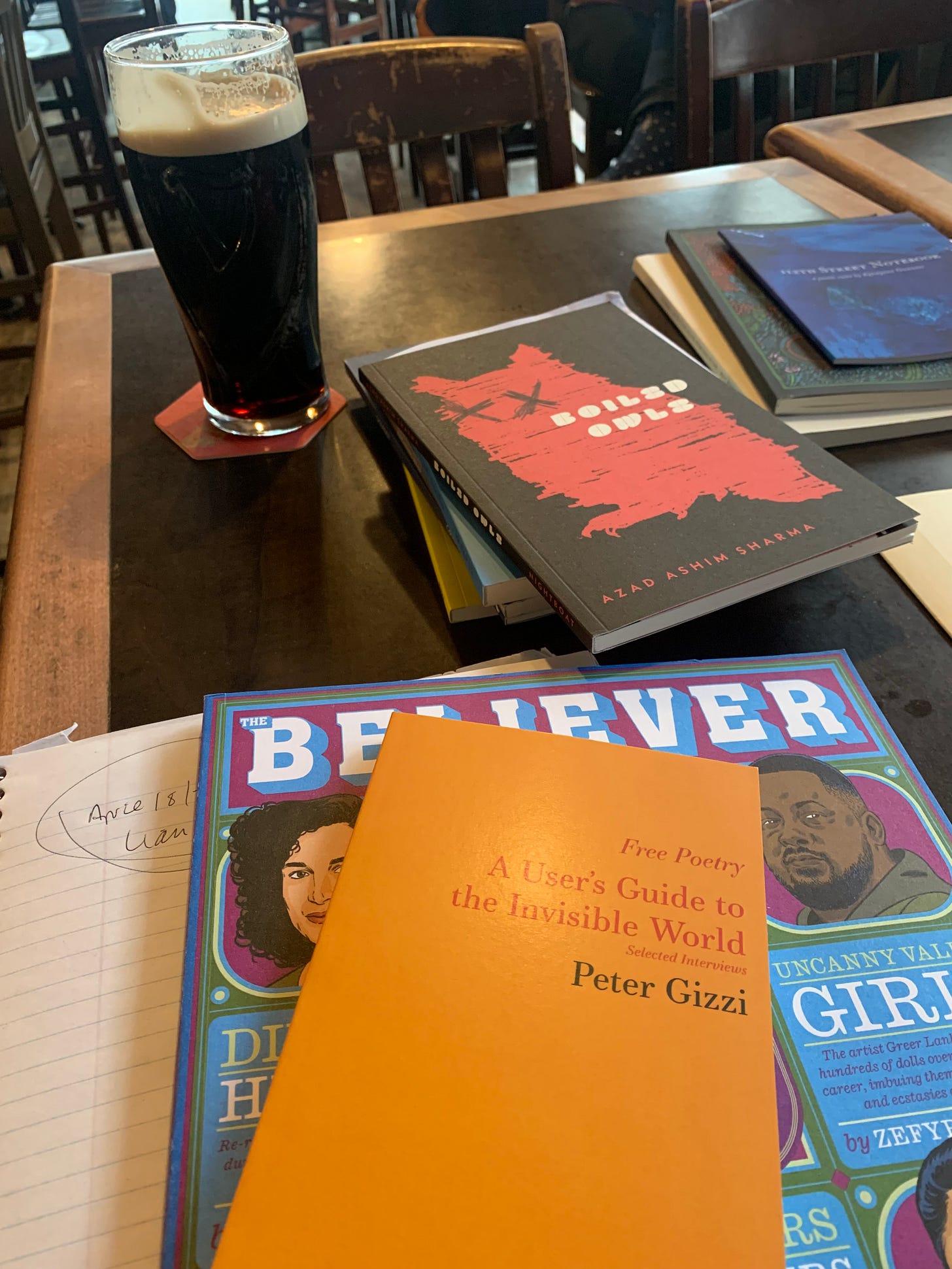

I’ve been thirty years writing in public spaces, more comfortable in coffeeshops, food courts or taverns than at my actual writing desk. The benefits of this, of course, is that I can get an enormous amount of work done while in an otherwise-distracting location, whether the hour-plus I used to get weekly in the St. Laurent Shopping Centre food court during middle daughter’s nearby gymnastics, or youngest daughter’s weekly thirty minutes of ukulele lessons on Sunday mornings at RedBird. With Rose in school over by St. Laurent and Montreal Road for three years (of which this is year two), I’ve even taken to sitting afternoons at the sportsbar by Christine’s work for an hour or two during afternoons, the proximity allowing but a ten minute drive to land at school pick-up. Proximity is important, after all, and it helps that most sportsbars are empty on weekdays, once the lunch rush is gone, and the after-work crowd hasn’t quite landed yet. And thus, my window.

*

“What I had intuited about the possibilities of the poem were confirmed by [Robert] Duncan and his circles (both at Black Mountain and in San Francisco): that a poem was obviously not a static commodity, it was an organic system living in time and space.” That’s a quote from near the ending of the first essay in Jackson Heights, Queens poet Lisa Jarnot’s FOUR LECTURES (2024).

I remember my pre-teen self walking down the neighbour’s laneway and repeating a word aloud so often that the word lost all meaning, reduced to the pure mechanics of sound. I do not remember the word. It is meaningless, now.

*

A copy of Kristjana Gunnars’ poetic suite 112th Street Notebook (2023) landed today. I’ve long been curious about the writerly notebook, one that curls in, around and through the thinking and business of writing, all the odds and sods that make writing happen, or don’t quite fit within those particular bounds of the writing itself. A notebook, one might reason, becoming boundless in comparison.

Aoife’s eighth birthday today. After a two-night Embers camp, I drove the three-hour-plus round trip to bring her home on Sunday, just in time to host fifteen young ladies for her party. Today is quieter, being a Tuesday. I walked her to school and continued west, spending the morning working poetry reviews at the coffee shop. Faith Arkorful, Bren Simmers, Hamish Ballantyne, Travis Sharp, Zach Savich, Joyelle McSweeney. In a certain way, there feels something comforting about still struggling to decipher the mechanics of poems and poetry collections after working so many reviews, attempting to understand writing from a few perspectives, first and foremost on its own terms. Why these choices over any others?

Around noon, Christine lands home from work, which means I’m to take the car for school pick-up for Rose. Up until then, I spend two hours in my usual spot at the sports bar right by Christine’s work, at Innes and St. Laurent, working on short stories, including the final touches upon this short story about crows. I chose this spot for its proximity to Rose’s school, but a ten minute drive. And for the fact of an Ottawa sports bar usually empty during early afternoon weekdays. Unless the Olympics, perhaps.

From Gunnars’ poetic suite: “The first step is the wonder. / First: I have to take everything with me.”