You hold me in your porcelain arms and I lie in your warmth. The room is imbued with steam, and the scent of eucalyptus. I am acutely aware of my breathing. In a life that seems to move so quickly, I savour this moment. Soon I stand, a puddle of draining water caressing my feet. A light flickers on my face, and I reach up toward the lamp to tighten the bulb. If there is no light, then my beauty is invisible, and I count among my beauty the deep creases around my eyes, around the edges of my mouth, the startling squareness of my once-round chin. I become older with each year, while the women who dance onstage with me, they never age. (“I Am Claude François and You Are a Bathtub”)

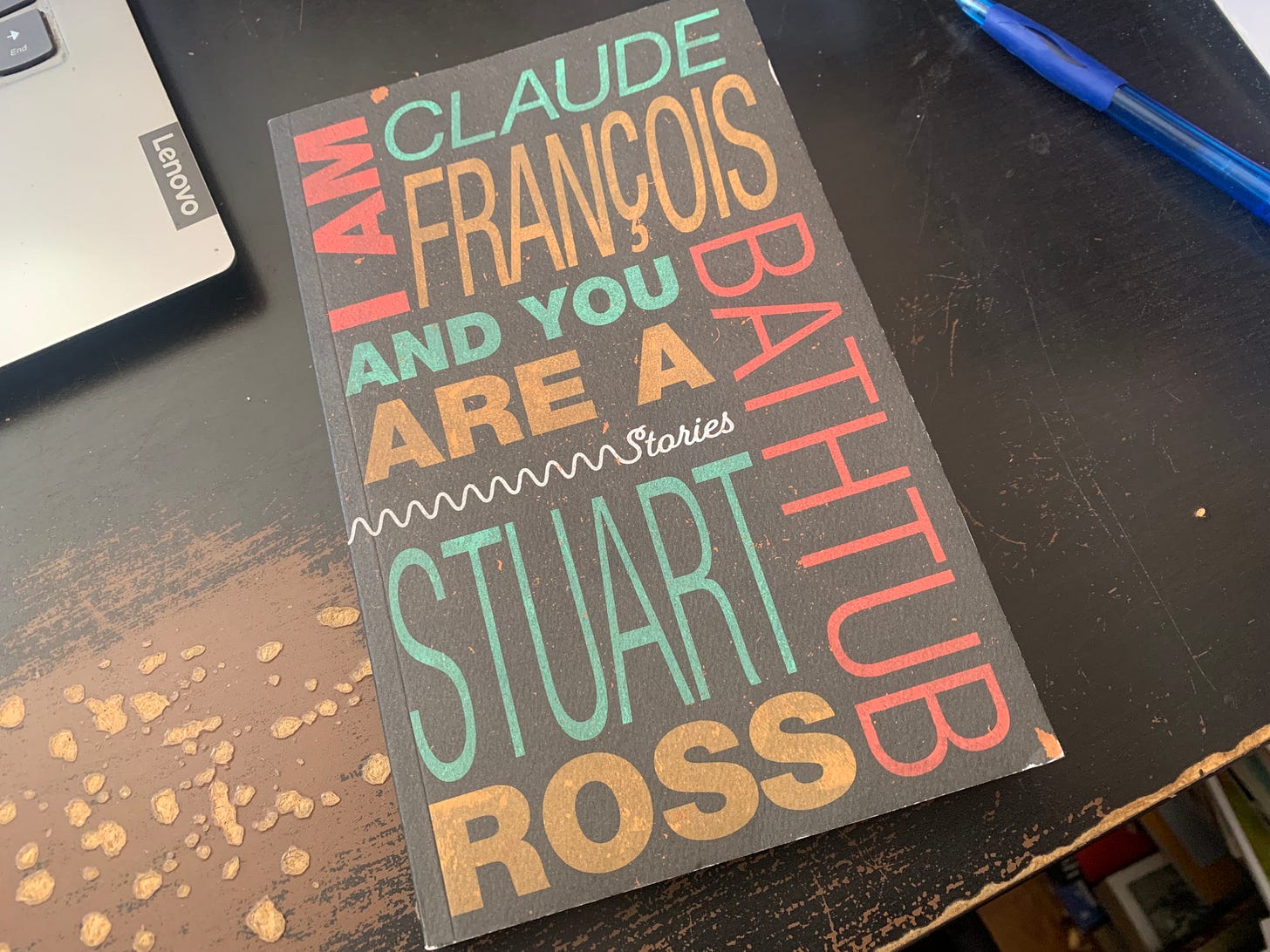

Further to bedtime rituals, middle daughter Rose and I read through Cobourg, Ontario poet, fiction writer, critic, editor, publisher and mentor Stuart Ross’ third collection of short stories, I Am Claude François and You Are a Bathtub (2022). I thought, somehow, that if Rose was open to reading the short stories of David Arnason, she might be ready to read through some Stuart Ross. As though one might ever be.

It might be easy enough to be distracted by Stuart Ross’ prolific output of poetry collections and miss that he’s published multiple works of fiction across the length of his writing career, from his prior short story collections Henry Kafka and Other Stories (1997) and Buying Cigarettes for the Dog (2009) to his novels Snowball, Dragonfly, Jew (2011) and Pockets (2017), as well as The Mud Game (1995), the collaborative novel he write with Gary Barwin. Back in 1982, Ross published the short novel Father, the Cowboys are Ready to Come Down from the Attic (1982) through his own Proper Tales Press, possibly one of the finer book-titles across Canadian literature (second only to William Hawkins and Roy MacSkimming’s infamous 1964 collaborative poetry title, Shoot Low Sheriff, They’re Riding Shetland Ponies!, a title that even Frank Zappa praised during an interview for Rolling Stone magazine). Father, the Cowboys are Ready to Come Down from the Attic was a title originally composed as part of the infamous 3-Day Novel Contest run through Vancouver’s Pulp Press (later, Arsenal Pulp Press), submitted to the contest the same year no winner was declared. As Canadian writer and playwright Tom Walmsley, by then well established in the Vancouver literary community, wrote in the introduction to Ross’ small volume: “There should have been a winner. This book should have been it.”

Ross’ poetry collection, The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky (2024), is described on the back cover as a miscellany, “a laboratory of poetic approaches and experiments,” and so too with I Am Claude François and You Are a Bathtub, a collection assembled out of pieces that are held by loose threads stitched together, a contradiction of structures that cohere together remarkably. The collection holds as a miscellany, but the prose is propulsive, especially through the reading voice of the author himself. In an interview Elena E. Johnson conducted with Ross for EVENT magazine, posted December 7, 2014 (conducted during the time some of these stories were written), Ross ends the interview by saying: “I read as scatteredly as I write.” As the story “La Papa” begins:

They’re all over the sidewalks, and they’ve got their kids, and their old people, and guys with white canes, and children with crutches, they’re spilling out over the curbs, right into the streets. It’s like the street is a continuation of the sidewalk, or else everything is just a big field of grass, but really it’s cement. They’re orderly, patient, no jostling, moving like a gigantic flowing amoeba, and I’m caught up in the wave.

In his literary work, whether through the short poem, short story or novel, Stuart Ross is very good at immediately establishing a foundation, however surreal or fantastical, from which his narratives are able to move. His work suspends disbelief, allowing his characters or narratives to move in any direction, able to write in such a way that any reader will trust to follow. There is an element of this reminiscent of the best work of British-born and Calgary-raised comic book writer and artist John Byrne, from his legendary runs across X-Men, Fantastic Four, She-Hulk or Alpha Flight: he could take his stories absolutely anywhere, because he knew how to back up the logic of what might otherwise seem impossible. Years ago, I reviewed Stuart Ross’ third full-length poetry title Razovsky at Peace (2001) for The Antigonish Review, and noted how Ross’ humour is sly and deceptive, often providing a distraction or red herring away from deeper purpose, simultaneously providing both meaning and surreal, even ridiculous, broad strokes in perfect harmony. As his piece “Remember the Story,” offers:

When you are a writer, the whole world is at your door. That’s what I’ve found. Or if not the whole world, then at least your friends. Every writer has his Andrew, tom, and Pete. Or if it’s a woman writer, her Andrea, Tamara, and Petra. (Isn’t it amazing how many girls’ names have an “a” at the end?) This is what we in the writing trade like to call our “audience,” or our “market.” It is they who consume or experience our art.

Ross’ work is known for his use of humour and the surreal, having moved his surrealism and absurdism elements into an undertone across his work, one that occasionally offers his surrealism into conceptual or structural realms. There are times his surrealism seems more abstract, compared to the work he was producing throughout the 1980s and 90s, during a period of “Toronto surrealism,” associating with a loose group of poets working in similar veins, including Alice Burdick, Victor Coleman, Gary Barwin, Lillian Nećakov, Gil Adamson, Kevin Connolly, Steve Venright, Mark Laba and Daniel f. Bradley, a number of whom were collected Ross into the anthology Surreal Estate: 13 Canadian poets under the influence (2004). As Ross wrote in his introduction to the anthology:

Such is the range of this small anthology: there are those here who feel they are writing a pure Surrealism, and even live the philosophy, and others who absorbed their surreal content through other sources: the Burroughs wing of the Beats, magic realism, Language poetry, the New York Poets, and neo-surrealists and absurdists like Joe Rosenblatt and Opal Louis Nations.

A self-described “sad sack,” Ross writes of shadows and depression, not as an edge but as a layering, whether set behind surrealist or absurd humour, or laid out directly, allowing his grief an articulation, without apology or misrepresentation. In his award-winning memoir, The Book of Grief and Hamburgers (2022), he admitted: “Here’s what I do: I put the word hamburger in my poems when things are getting a little too heavy. Because the word hamburger makes you laugh. So this manoeuvre makes a heavy poem lighter. You can lift it more easily.”

There’s an infamous quote by the late British comedian Marty Feldman (1934-1982), who once described British humour as composing a scene that opens with five guys in carrot suits. When someone walks on without a carrot suit, the action then needs to work to explain why that sixth character isn’t wearing one. You can see it from the opening of the title story to Stuart Ross’ I Am Claude François and You Are a Bathtub, or his story “There Were Shingles Beneath Their Backs,” also included in the collection, that begins:

Howie was lying on the roof of the house in some damn neighbourhood he knew he’d been in before, but he couldn’t recall when he’d been there or where he was. Mr. Cage lay beside him, his breathing shallow. They both felt the same breeze lick at their necks and foreheads. When they opened their eyes, they looked at the same clouds blotting out the same stars, and recognized the occasional pterodactyl winging by, its black silhouette just visible against the slightly less black of the clouds.

Really, the whole of Stuart Ross’ work could almost be seen as a series of articulations around and against perception. His stories often know far more than his characters do, as Ross is able to communicate narrative in such a way to allow the reader an insight that even they may have missed, or deliberately overlooked. Through the story “Skunk Problem at the Foot Booth,” for example, the entire tension emerges through the disconnect between the narrative of the story and how the main character is somehow misunderstanding what has occurred, with the added layer of whether or not this is a deliberate choice on this particular character’s part as a coping mechanism, or emotional break. As part of the interview “Stuart Ross on Experimental Novels, Big Ideas in Short Word Counts, & Juggling Multiple Projects” for Open Book, posted November 14, 2017, he’s asked the question: “What defines a great book, in your opinion? Tell us about one or two books you consider to be truly great books.” He responds:

I’ll stick with novels, and I think the great ones define themselves. The author is bold or reckless enough to ignore current fashion and let the book be what it needs to be. There is no padding. The sentences are varied and excellent. The books are unpredictable. Toby MacLennan’s 1 Walked out of 2 and Forgot It is a great book. It is uncompromising and crazily evocative. Beautiful. On the other end of the size spectrum is Frederick Exley Jr.’s A Fan’s Notes, a sort of fictionalized memoir from 1968. It is sprawling, anarchic, funny, and painful. I mean, it’s about a football journalist and I hate sports and I loved this book. I’m going to squeeze in one more: Joko’s Anniversary, by Roland Topor, from 1970. Some guy gets eight people stuck on his back. Tragicomedy ensues. Written in quasi-play form, it’s insane and was another that inspired me as a teenager.

With his surrealist undertone, his work is about perception, and the unsettling of what it is you think you understand. In the opening story, “The Elements of the Short Story,” he offers the deliberately misspelled “Alice Munroe,” an extra letter that knocks the reader out of the narrative slightly, which makes one wonder, exactly, what Ross is working at, beyond the obvious elements of humour, and possibly not wishing the reader to be distracted by his particular commentary as critique. As part of the roundtable discussion included at the end of Norm Macdonald: Nothing Special (2022), the posthumously-released final stand-up special by the late Canadian comedian and actor Norm Macdonald (1959-2021), Conan O’Brien spoke of how Macdonald would deliberately mispronounce words when a guest on his Late Night show, to purposefully knock listeners off-balance. Through jarring expectation, the listener is forced to jettison lazy thinking, forced to take the presentation of what is being said on its own terms. Basically: when reading Stuart Ross, you suspend belief. You have to pay attention. As Ross’ story “There Were Shingles Beneath Their Backs” offers:

“Has it come to this?” Howie said quietly.

Mr. Cage let his eyes fall shut, having had his fill of the clouds.

“In what way are we related?” Howie asked.

A short explosion in the distance. A car backfiring, a gunshot, a brick hitting the pavement.

Mr. Café cleared his throat. He could just barely speak through his cancer now. it made his clothes fit better but it made it hard to speak. He stuck out his tongue to find some cool air. he had something to say and needed to cool his throat.

A drop of rain fell. It landed on his tongue.

Thank you for this insightful appreciation of a superb writer whose books are intelligent, thoughtful, moving, and so frequently FUN. I hope and trust your essay will introduce more readers to the wonder named Stuart Ross!

Great interpretations