A book about how difficult it is to change, why we don’t want to, and what is going on in our brain. A book can be about more than one thing, like a kaleidoscope, it can have many things that coalesce into one thing, different strands of a story, the attempt to do several, many, more than one thing at a time, since a book is kept together by its binding. A book like a shopping mart, all the selections. A book that does only one thing, one thing at a time. A book that even the hardest of men would read. A book that is a game. A budget will help you know where to go. A bunch of us met to have dinner that night, but I left and walked off by myself, bought the silver ring, a bag of chips, then sat in the main square and bummed a cigarette off an old French man, then continued to sit there for many hours until the man with the bulgy eyes came to sit next to me and flirt. A bus came which was going to the ferry, but because I hesitated before getting on, it drove angrily away. (Alphabetical Diaries)

I’m fascinated by how Toronto writer Sheila Heti employs elements of autofiction, but as a means through which to explore narrative expectation and narrative structure, and those central questions of how, exactly, we should be in the world. When speaking of contemporary autofiction, one might mention authors such as Michael Winter (specifically those first two short story collections and debut novel) and Billy-Ray Belcourt (there are further examples, I’m sure), but one could argue this is all simply a variation on what some writers have been doing for years, whether through the creative non-fiction of Brian Fawcett, Myrna Kostash or Elizabeth Hay, Fred Wah’s exploration of biotexts, Dany Laferrière’s essay-novels, or the extended works of Bernadette Mayer and Gail Scott, all of whom have utilized some variation on working personal details as a means to and through to an end, as opposed to an end unto itself. As Miranda July offered as part of an interview conducted by Ross Simonini for The Believer (issue #113, fall 2015): “I so admire people who can write from their actual life—Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner—and it looks so easy and why can’t I do that? But I need more distance. I need a story, some kind of veil to work through.”

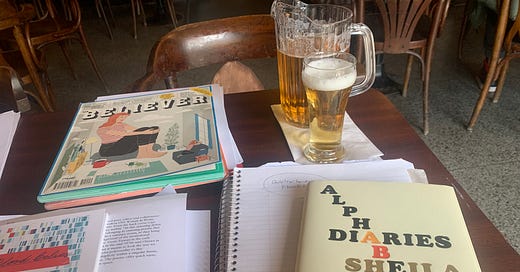

The cover flap of Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (2024) writes that “Sheila Heti collected 500,000 words from a decade’s worth of journals, put the sentences in a spreadsheet, and sorted them alphabetically. She cut and cut and was left with 60,000 words of brilliance and mayhem, joy and sorrow. These are her alphabetical diaries.” The sentences assembled thus might at first appear scattered, even random, to the point of ordered without meaning or purpose, until one moves deep enough through the text to catch small echoes; small threads and echoes, through which one begins to garner a kind of portrait of the author, even if that portrait might only cohere and exist within the reader’s imagination (and with as many potential variations on that portrait as there might be readers).

From The Middle Stories (2001) to Ticknor (2005) to How Should A Person Be? (2010), Heti’s books dismantle genre from the inside, and rebuild narratives into impossible shapes that reveal far more than the limitations of genre might ever have allowed. Her books are filled with story scaffolding, even while twisting the fable across The Middle Stories, or the expectation and purpose of the modern/postmodern novel through Ticknor. It was through How Should A Person Be?, Heti’s exploration of self and the narrative self, writing a semi-fictional “Sheila Heti” and her semi-fictional friends, that she began to expand on some big themes: quite literally, how to live and be in the world. One could spend a whole lifetime within that singular question. In the forward to The Chairs Are Where The People Go, subtitled “How to Live, Work, and Play in the City” (2011), a title Heti wrote with Misha Glouberman, she wrote:

Misha Glouberman is my very good friend. Years ago, we started a lecture series together called Trampoline Hall, at which amateurs speak on random subjects in a bar. He was the host, and I picked the lecturers and helped them choose their topics. I was interested in finding people who were reticent about talking, rather than showy people who wanted an opportunity to perform. After three years of working on the show, I quit, but Misha kept it running.

A few years later, I really missed working with Misha, so I decided I would write a book about him. It was called The Moral Development of Misha. I got about sixty pages into the story of a man who wandered the city, who was nervous about his career and his life, yet was a force of reason in any situation. Work on it stalled, however, when I couldn’t figure out how to develop him morally.

Worse than that, I never found the project as interesting as talking to my friend. I have always liked the way Misha speaks and thinks, but writing down the sorts of things he might say and think was never as pleasurable as encountering the things he actually did say and think. If I wanted to capture Misha, in all his specificity, why was I creating a fictional Misha? If I wanted to engage with Misha, why not leave my room and walk down the street?

One day, I told him I thought the world should have a book of everything he knows.

Heti, as she herself offers, writes not to tell or show you how to live, but to wrestle with the very question of asking how we should. Perhaps this is part of a thread, or a trend, of writing, seeking to dig into the moral obligations of living; of questions and questioning, even before seeking out what questions, in fact, we should be asking. Think of Miriam Toews’ Women Talking (2018) as another example, as certain writers drift from (ironically enough, in the case of Women Talking) the cinematic novel to books that lean more philosophical. As Heti writes in Alphabetical Diaries: “A sudden happiness pierced me. A sweet kiss with him in front of the grocery store on Bloor, he kissed me on my cheek and I kissed him on the lips, just a sweet, little one. A tendency to idealize the past—that’s me.” The questioning is essential, and her books respond. There is something, perhaps, that Heti’s own thinking is trying to get to, one step and one book at a time. In an interview conducted by Thea Bowering for The Capilano Review (3.22 / Winter 2014), “‘a portrait of thinking’: Sheila Heti and Thea Bowering on the phone,” Heti responds:

If you’re just trying to make something beautiful, which we all are—beauty is compelling—you’re going to go towards a certain shape, let’s say, or towards a certain narrative structure. You’re trying to do something well. But the only way you can do something well, I think, is if at first you have some model in your mind of what the good is. To do something that doesn’t move towards this picture that you have in your head of what you want the work to be, that’s a very difficult thing to do. And you kind of have to trick yourself, and be vigilant. I mean all editing is always in the direction of greater clarity, towards communicating in a more precise way that’s related to beauty. To try to edit, not in the direction of beauty is really hard. But all of that felt really necessary for me because, I mean it seems crazy to say that this is true of somebody so young, but I felt that I’d reached a dead end. When I was working on Ticknor I was really trying to make something absolutely perfect and I knew that I couldn’t do that again. I felt it would be dead if I tried to do that again. In truth, How Should a Person Be? isn’t the book of mine that I like the most. I prefer Ticknor or even The Middle Stories. How Should a Person Be? is very much against my innate aesthetic. It makes me uncomfortable to have put out something that isn’t, in my mind, beautiful or perfect, even though this book has had the biggest response. So I think there is something to be said for making yourself uncomfortable, and for questioning your instinct to please some internalized aesthetic criteria. Maybe there’s something lifeless about that, on some level.

If Heti’s framings are conceptual, then any asides will exist coherently within that same structure, offering a framing of thought, philosophy and narrative. Through a montage of asides, her narratives work in all directions simultaneously but always allowing a cohesive straight line, returning back to a central thought, from which each next action sits. Each book provides a variation on the same abstract and philosophical questions that can be directly applied to multiple situations: the ability to articulate an abstract with enough grounding that any reader might identify. “Sitting opposite Annie,” she writes, near the end of Pure Colour: A Novel (2022), “Mira now wondered if this was also true of herself and Annie, that sometimes a person is meant to move forward in the world with the one they love at a distance, and that the distance is there to make it more beautiful. To find the right distance from everything in life is the most important thing. To stand at the right distance, like God standing back from the canvas—for you can’t see anything if you’re too up close, and you can’t see anything if you’re too far back. So that is how she sat with Annie, there in the chocolate shop, across from her at the table. From across the table, Annie had managed to pull Mira back into life—back into this human life.”