I think about my own childhood, when Clayton’s stories first twined themselves into my consciousness. Fragments of the past forming the natural counterpoint to my own experience. I suddenly remember the morning sunlight falling into the parsonage vestibule through a tiny round stained glass window high up in the stairwell. Light broken into coloured shapes, filtering through the railing and spilling down the stairs.

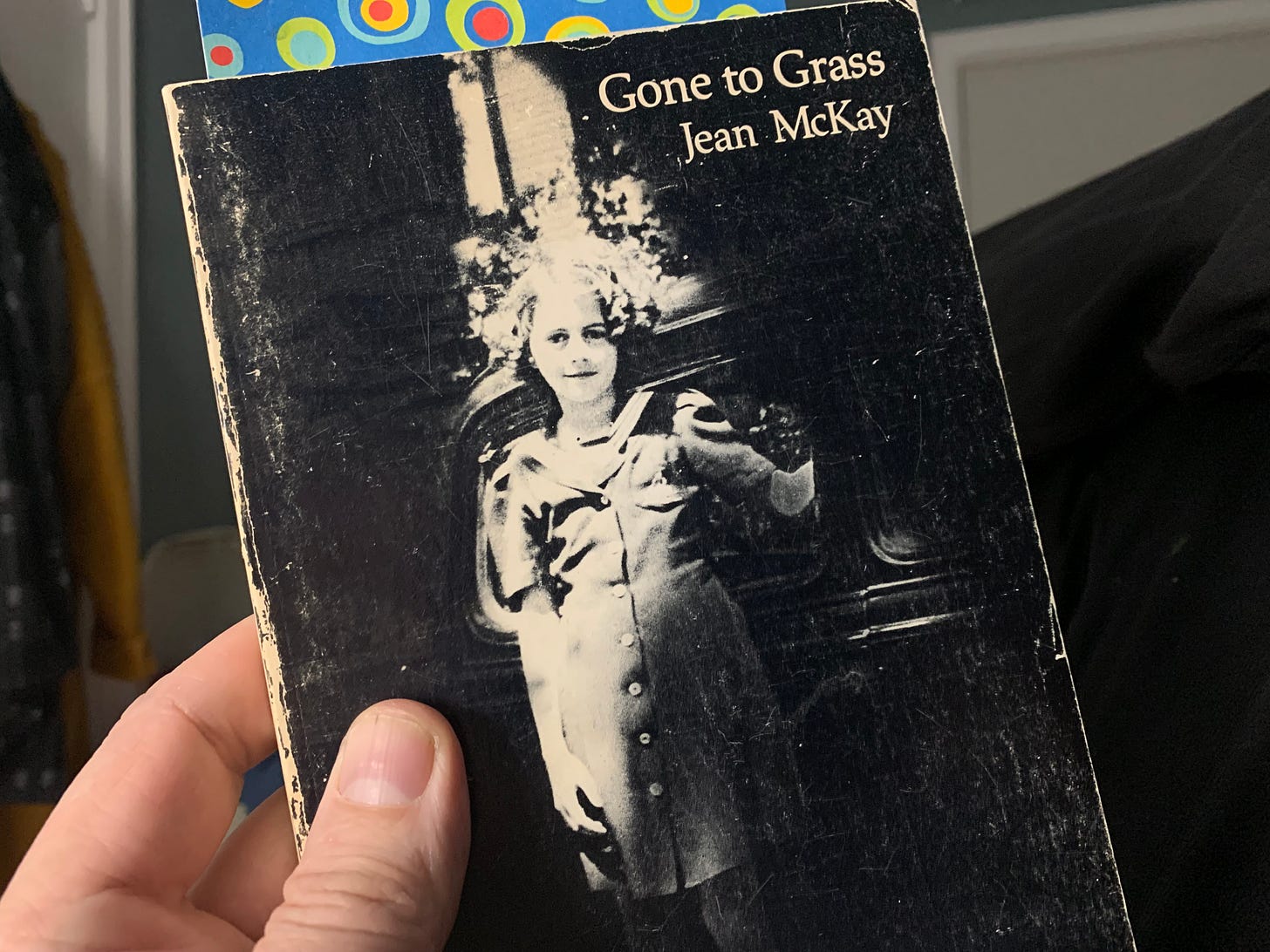

Lately, as part of our nighttime reading rituals, I’ve been reading aloud London, Ontario writer Jean McKay’s prose memoir on her father, her self-described “autobiographical novel,” Gone to Grass (1983), to our ten year old daughter, Rose. This is a book I originally read back in 2016, across those hospital hours waiting out those long hours up to the birth of her younger sister, Aoife. As McKay responded via email at the time: “That’s a first for me. I’ve had people return to Gone to Grass when people have died, but never (that I know of) to accompany a birthing.” I’ve been moving through Canadian literature as part of nighttime rituals with Rose for a while now, testing out her tolerance, following the two years we went through the entirety of the Harry Potter series, and into the Percy Jackson series (which she ended up reading on her own). We’ve explored short stories by David Arnason, Stuart Ross, Leon Rooke and American writer Joy Williams, plucking titles from my personal library to see what might strike. We’re half-way through McKay’s book, with the occasional pause for me to explain a reference, or as Rose offers her own commentary. That’s so mean, she might say of the described behavior of a neighbour, or Why would they do that?

I caught a reading by McKay as part the 2004 Windsor Festival of the Book and remember being amazed; where had she been all this time? One of the co-founders of Brick: A Literary Journal, McKay has certainly kept a low profile, only occasionally releasing yet another striking prose work into the ether, from Gone to Grass to the short story collection, The Dragonfly Fling (1992), to Exploded View: Observations on Reading, Writing and Life (2001). There’s even a chapbook I have around here somewhere, The Page-Turner’s Sister (1999), the first title I would have seen of hers, and her most recent, that I’m aware of. How can a writer with a blurb from Annie Dillard that reads “Jean McKay is one of North America’s finest writers” be so invisible, so disappeared, so immediately unknown? McKay’s prose is as smart as any I’ve seen, demanding the strictest attention, as she weaves through concepts, memoir, narrative and relation with remarkable ease. An online biography for McKay includes the tidbit on Gone to Grass and The Dragonfly Fling, how “both of which were adapted for the stage,” which is a curiosity. How did the material shift for the stage? Was it McKay or someone else who worked the adaptations? Her only title that might still be in print, Exploded View sits as a striking abecedarian of flash fictions, collecting fragments of observational, meditational stories set up in an unlikely pattern. The stories are quite unusual for in just how they strike, and tell their larger stories, twisting and turning into each other, allowing her sage observations to float to the surface.

Gone to Grass is an accumulation of first person prose-recollections on childhood that focus on the author’s father, Rev. Horace Clayton Burkholder (1902-1967). “The next summer, my mother was reading a biography of Lloyd C. Douglas,” McKay writes, to open the collection, “written by his two daughters. She looked up from the book and said ‘Someday, Jeannie dear, I hope you’ll write something about your father, so people will know how wonderful he was. He was a happy man, a very happy man.’ Apparently Lloyd C. Douglas was also a wonderful man.” The writing is expansive, and an enviable example of capturing something so close, so heartfelt, in a way that it allows itself a fully-realized work, able to communicate memory itself, something so deeply personal, ephemeral and distant. Offering lengthy anecdotes on and by her father, she writes from the perspective of her childhood self, allowing the wisdom of distance to chime in when required, but without stepping on those earlier understandings.

There is a feature that her prose shares throughout her three published books: not simply an ease of a relatively straightforward prose with lyric elements, but how each of her stories wrap around each other, interlinking not quickly but eventually, writing out memories, moments, grocery lists and domestic matters, the surreal aspects of small narratives, and what happens between a person and perhaps another person. The level of recollected detail, of stories McKay’s father told, seems remarkable to me, and there is an element of these stories she tells of her father that also feel very familiar, of a Protestant household in a particular era of rural Ontario. Despite McKay being roughly the age of my parents, these are threads in Gone to Grass familiar to my own eastern Ontario childhood; sections that struck deep, triggering a wealth of tangible memory, down to the sounds and the smells of the musty church interior, such as her section on communion services, mid-way through the book:

I was a lot older before I realized what a secular communion the United Church offered. McGavin’s white bread (from which I myself had cut the crusts) and Welch’s grape juice.

There were pieces of wood screwed into the pews beside the hymn book racks, each drilled through with three holes to receive the empty glasses. My mother felt people should hang on to their glasses until the end of the services, because the tinkling sound of glass against wood destroyed the mood. Of course no one ever did. Some churches put a notice in their bulletin. Please retain your glasses until … The wealthier ones simply lined the wooden holes with felt.

To me, the noise was special. It had a tropical air about it, like the whispering of birds; the satisfied sigh of people who’d just had a focused moment of God. I always wanted Protestantism to be more exotic than it really was.

Gone to Grass sits as an interesting pairing with the prior book I had read to Rose, Diane Schoemperlen’s Double Exposures (1984): two works of first-person prose from Coach House Press that appeared a year apart, each composed as a sequence of self-contained childhood recollections (although Schoemperlen’s a work of fiction) around small-town Ontario. At the time Gone to Grass was originally published, reviewer Margaret Stobie offered this as part of her review in Canadian Literature #102 (1984), a book she called “beguiling in the quality of the prose […].” “Any tendency towards the sentimental is sharply checked, however,” she writes, further on, “both by Jean McKay’s superb artistic sense and by the irreverent laughter of Clayton, the story teller, as in his Theory of Extra Parts: ‘There are more horses asses in the world than there are horses.’ The tone of this little book — it’s not much more than a hundred pages and not many of them are filled — is also set by the perspective of the narrator, that of a young girl who could record without comprehending: ‘There was something mysterious, something that couldn’t be spoken, that passed about above me, up there with the adults.’ And it is the in-comprehension that gives another sense of beguiling, the masking of reality.” There is that feeling of comprehension occurring as the stories are told and retold, allowing for the mutability of not only memory, but of what those recollections provided. Even as you, the reader, might experience these recollections, the narrator is attempting to figure it all out herself, watching her thinking in real time. “Suppose, suppose.” McKay writes, “There was no right answer. There was no answer at all. Just a little conundrum come alive in my mind.”

Lovely!