My focus here, though, is the small small press – publishing that occurs in someone’s home or garage. People who, like me, have expended time, money, and friends doing this thing they love. People who fold and staple on their kitchen table, mass-photocopy at their workplace after hours, leave a trail of matchbook-size poetry magazines in telephone booths and on subway seats around the city. Joe O’Sullivan, who displayed his a scenario press output at the first Toronto Small Press Book Fair in 1987, sold poems he’d sealed into walnut shells. Poems on cheese sandwiches were also for sale nearby, and poems on the soles of old running shoes. There were mimeographed rants, tiny novels in pamphlet form, and – at Nicholas Power’s Gesture Press table – comic strips about sentient potatoes.

Stuart Ross, Further Confessions of a Small Press Racketeer

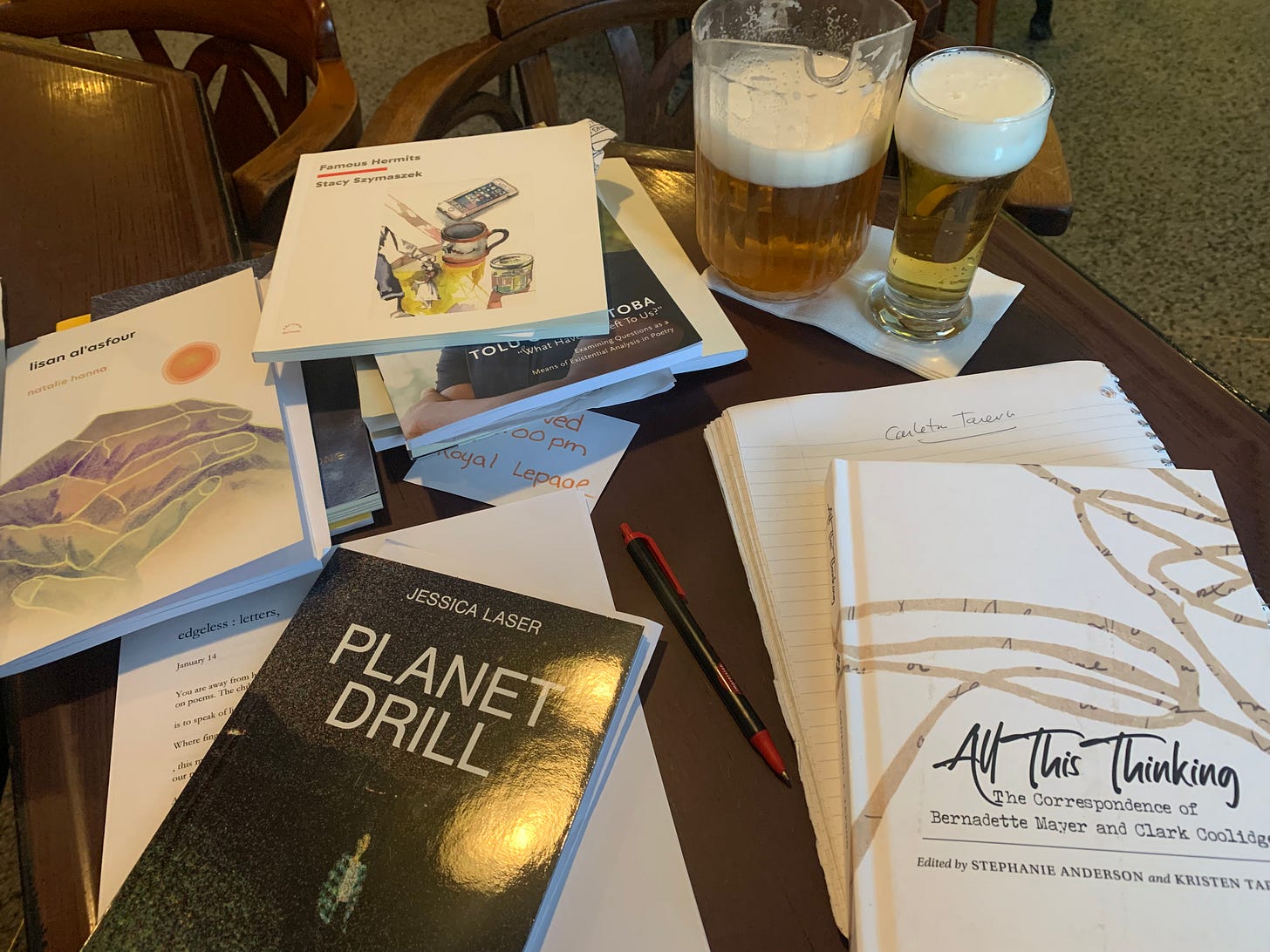

I am in my house and you are in your house too. Your house, your apartment, the space of your room. I am at the Second Cup at Bank and Randall; you are at your kitchen table. Virginia Woolf spoke of a room of one’s own, focusing on the requirement of a physical/temporal space in which to properly think, and for the longest time I hadn’t that, although who does in their twenties: a sequence of domestic or roommate situations that didn’t allow for a particular solitude. For twenty-plus years, everything I composed was in public view, public spaces: from coffeehouses, food courts and libraries, taverns and Greyhound stations. Now I can sit two hours in a Tim Horton’s on St. Laurent, awaiting my middle daughter attending a Laser Tag birthday party next door. I can sit a few hours from mid-afternoon onwards at the Carleton Tavern on Parkdale, two or so blocks from where I was born. The first drafts of poems or stories or essays or reviews I’ve generated on Air Canada heading to Vancouver, or the Greyhound to Toronto, back when we had those. This craft as much a muscle as anything. You have to work it, work at it. Build it up. Malcolm Gladwell’s ten thousand hours, offering the examples of The Beatles in Hamburg or a teenaged Bill Gates, working overnights in an otherwise-empty computer lab. My twenties and thirties were spent in Centretown and Lowertown public spaces: daily stretches at the Second Cup at Bank and Somerset, afternoons in the Rideau Centre’s prior food court, evenings working on prose at Ottawa’s original Royal Oak Pub. My approach originated in a particular ethos of farm-labour, my youthful attendance of that same patch of land as my father, as his father before him, and his before that, all of whom woke daily to respond to the requirements of each particular morning. They shaped their own days, around the foundation of twice-a-day milking. The near-decade I spent—five hours a day, six days a week—at the Dunkin’ Donuts at Bank and Gloucester from 1994 onwards until the business closed down, and I subsequently landed at fourteen years’ worth of mornings at the corner window of that particular Second Cup. Sketching longhand, a handful of poetry titles in tow and daily newspapers. The shape of my days and the shape of this room. Why, you might ask yourself, am I telling you this?

At some point in my youth, I caught a quote attributed to Margaret Atwood: if you want full-time out of it, you have to put full-time into it. When my eldest daughter was small, I ran a home daycare in our small apartment. Imagine: ten hours a day five days a week with her and two others, as I wrote three nights a week from seven pm to midnight at a coffeeshop a few blocks north, at Elgin and Gladstone streets. As I’ve said prior, the waitress, Zana, would brew one pot of coffee for me, and another for everyone else. I wrote, and I wrote, working longhand some thirty to forty to fifty drafts of each poem.

Toronto writer Brian Fawcett used to boast of composing his hockey novel while awaiting his teenaged daughter’s pre-dawn hockey practices. I can imagine Brian sitting the stands with coffee and a notebook, sketching out complaints amid his daughter’s apparently impressive hockey skills. Or Vancouver writer Wayde Compton, who began writing fiction in the cafeteria hospital, during a hospital stay and convalescence. Even after he was released, he found the space generative, and would return daily up that hill via BC Transit. However the work gets done.